Above: David Sipress, on the left, with Sam Gross, who Mr. Sipress calls “the funniest cartoonist that’s ever been.” –Photo: Ken Krimstein

We don’t see many memoirs from New Yorker cartoonists. Peter Arno started one, but it never went further than lists of names and snippets of memories to explore. Bruce Eric Kaplan wrote one, I Was A Child — “profusely illustrated” according to the publisher. Edward Sorel recently published Profusely Illustrated: A Memoir; Michael ffolkes published a memoir in 1995 — ffundamental ffolkes: An Autobiography — but I’ve yet to get my hands on a copy (from the few pages I’ve seen it looks heavily illustrated). I’m working on a New Yorker-centric memoir, with more text than graphics. Jack Ziegler wrote a memoir, still under wraps. Dana Fradon reportedly worked on one as well. Art Young wrote a memoir (“His Life And Times”), but let’s face it, with nine New Yorker cartoons spread out over eight years, his published world was clearly elsewhere. James Thurber never wrote a full-on memoir, but we can piece together much of his life from reading Thurber Country, The Years With Ross, and, of course, My Life And Hard Times.

What I’m getting at is that there have been just a handful of published memoirs from the over six hundred (and counting) New Yorker cartoonists plying their trade since the magazine began publishing in 1925. And of those published, the use of illustration has figured largely in the memoir-izing.

What I’m getting at is that there have been just a handful of published memoirs from the over six hundred (and counting) New Yorker cartoonists plying their trade since the magazine began publishing in 1925. And of those published, the use of illustration has figured largely in the memoir-izing.

The publication on March 8th of David Sipress’s What’s So Funny: A Cartoonist’s Memoir is then a special occasion [read an excerpt on newyorker.com, “The Day I Declared Myself A Cartoonist”]. Although there are plenty of cartoons in the book, there is far more text. That in itself, as just noted, is an unusual thing as far as New Yorker cartoonist memoirs go.

With David now having shared with us a great deal of his life — both his personal and his pen life — it seemed the perfect time to get him talking even more about his New Yorker world — a world that he finally entered in 1997, when the magazine first bought a cartoon from him after a quarter century of rejecting his submissions.

I first met David in the late 1970s at a cartoonist event at the Lotos Club on Manhattan’s upper east side; he noticed my name tag and wondered if I was related to Janet Maslin [I’m not, as far as I know]. Over the years David and I have run into each other and chatted innumerable times, but this was the first time we’d had an extended conversation. In preparation for this interview I looked at every one of his New Yorker drawings (something I do before interviewing any of my colleagues). It was an experience I recommend for anyone wanting a merry ride through years — decades– of accomplished work.

What follows is an interview conducted mostly on the phone, with some email back-and-forths helping to gather stray ends. It is lightly edited, with mostly my “ums” and “uhs” removed, and the occasional sentence edited for clarity. We spoke on a grey overcast Thursday morning in January. David was in his studio in Brooklyn.

Michael Maslin: David, how are you this gloomy Charles Addamsy day?

David Sipress: I’m doing fine. It’s a weird time because there’s a month til the book comes out, and there’s all this stuff I’m doing — I’ve done a number of interviews. I’m excited, I’m nervous…

MM: It’s such a fun time when one’s book comes out. You did a great job in your book of creating the era surrounding your early life; it’s fun to read, but, of course, there are not fun parts; it’s really different as cartoonists memoirs go, and that’s some of what we’ll talk about.

I know you work in a studio, away from your home. I think that’s sort of unusual these days. I believe most of our colleagues work at home. I’ve always wondered what it would be like to work away from home. What’s that like? I know it’s necessary for you.

DS: The main reason I have a separate space — and I’ve done this as long as I can remember — is a practical reason, because if I worked at home I’d never stop working. And that could be a problem for the relationship [laughs]. But the main thing, I’ve always done this because I’ve always had a certain amount of residual guilt about my career choice, given my father’s expectation for the sort of serious important work I’d do in my life after all the money he spent on my education.

I turned out to be a cartoonist, but a cartoonist who feels guilty about being a cartoonist, because I probably should be a lawyer or an ambassador, or something that. So by having a separate space I give myself the illusion that I’m going to the office everyday, to that real job I really don’t have. It’s funny, but it actually is true. It really gives me a sense that what I’m doing is grounded in reality. Because, as you know, as a cartoonist, it can sometimes feel like you’re all alone, doing something nobody cares about or pays attention to. Coming here I just feel, “Okay, work day. Job’s started.”

MM: You’ve disciplined yourself.

DS: Absolutely. Plus, I love it. I think I say in the book: all those desert island cartoons, so much can happen when you’re in a quiet separate place that can’t happen otherwise. I find that thinking up cartoons is a kind of meditation, and being in a quiet separate space where dishes are clanging in the kitchen, and the cat isn’t crawling all over me, is a big step towards opening the doors to perception, and allowing me to let those ideas come.

MM: I agree. I work at home, but I find that the best things happen for me are when I’m just waiting. It’s always good if you can just be and not have dishes clanging.

Can you describe your studio a little — what the room’s like.

DS: It’s a good size space, I’d say about 300 square feet, and I’ve got two desks: the desk that I’m at now where my computer is, and then behind me is my light box and my drawing desk. I sit at the desk I’m at now when I’m trying to come up with stuff. And I sit at the other desk when I’m executing stuff.

On the walls I have a favorite poster my wife and I got at Paris years ago from a surrealists show at the Pompidou which I love. It’s got a Magritte image on it. I’ve got a framed page from The New Yorker my wife gave me of my first cartoon in The New Yorker. I’ve got a cartoon by Danny Shanahan, a cartoon by Arnie Levin… I’m looking around… a cartoon by Bob Weber, a cartoon by Mick Stevens…all hanging on the wall, all trades I’ve made. I have, on another wall, my Gag Cartoonist Of The Year Award from the National Cartoonists Society [David won the award in 2016]. And then files, as you can imagine, chock-full of roughs and stuff that never got published. And piles of stuff that has gotten published. That’s pretty much it. It’s a nice clean quiet space. At home I have a lot of problems with neatness, somehow here everything’s ship-shape.

MM: I’m jealous of your Arnie Levin drawing [the Spill‘s cartoon collection includes work by Stevens, Weber, and Shanahan]. I’ve been trying to trade with him for years.

DS: Oh, it’s so wonderful. I don’t know if you remember it, it’s the one about the Lord of the Dance.

MM: Probably if I saw it I would. I love Arnie’s work. I remember the moment at some party when I told him how important his work was to me, and it didn’t go over well.

DS: He’s such a nice person he doesn’t do well with that, but I understand why you also would be drawn to him because his style, his use of line, the simplicity of his work is so remarkable.

MM: It’s beautiful, yeah.

DS: I admire him enormously.

MM: I have a list of questions, and I’ll try to get through them before I exhaust you. One of the many things about you that’s so interesting is this 25 years before you got in [to The New Yorker]… just blows my mind, you know. It’s hard to grasp how you endured 25 years. I endured about 7 — I cant imagine tripling that and then some. What was your mind set then, what were you thinking?

DS: I think if you think about it, it’s not difficult for you to imagine. If you’re a cartoonist, who does what we do — a single panel cartoon — there’s always only been The New Yorker, and then everywhere else. And so, there’s no point in giving up because it’s impossible to conceive of life without being in The New Yorker if we do what we do. I was doing the cartoons anyway, and so, at some point, I forgot all the rejection, and as a kind of fourth habit, put an envelope in the mail or brought an envelope in. Maybe not every week — twice a month probably, all those years. I became a little inured to the pain.

After awhile I would say to myself, “David, don’t have any expectations. You know what’s going to happen.” It sort of became a way of life. I always believed in my work, and in spite of my tendency to think the worst of myself at times, I did think I was really good. I would look in the magazine and I would see people and I would think, I could do that, I’m as good as that. And I kept going all that time. I didn’t really have my confidence affected by the rejection.

MM: Did you ever go in and talk to Lee and say, “What’s going on?” [Lee Lorenz was The New Yorker‘s art editor, and later cartoon editor, from 1973 through 1997].

DS: First of all I could never get in to talk to him. I’m sure you remember it was really difficult to get in to see him if you weren’t in the magazine, and so I didn’t really have a way in.

What was he going to say? He clearly had a problem with my work, or, I don’t even know if he paid much attention to it.

A few years ago there was an event at a museum here in town and [laughing] he just said how much he loves my work.

MM: Wonder why he didn’t love it 25 years ago…

— Right: The first Sipress collection, 1981

DS: When I was growing up, I didn’t just want to be a cartoonist, I wanted to be a New Yorker cartoonist. I didn’t even consider any other kind of cartoonist — that’s what I wanted to be. I was never gonna let that go. I hate to harp on the 25 years because it’s such a sad pathetic story, but really my spirits were not destroyed during that, I was optimistic. I knew that one day something would happen.

MM: I think it’s great — I don’t think it’s sad. It was a wonderful commitment. You and Peter Vey share that [kind of commitment] — although I don’t believe it was as long a wait for Peter.

You know there’s a guy who has a book out about being the longest active rejected cartoonist.

DS: Who is it?

MM: His name is Roy Delgado.

DS: Oh yeah, I know his work.

MM: He put a book out called A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The New Yorker. So he’s made a thing out of not being accepted after decades and decades.

DS: All I can say is, in my life, thank god for Bob Mankoff [The New Yorker‘s cartoon editor from 1997-2017] because it happened right away, as soon as he took over. I’ll always be grateful to him for that.

MM: And that leads me to this… I looked up your class — your class of 1998, and all the cartoonists you came in with: Chris Weyant, Pat Byrnes, Nick Downes, William Haefeli, Marisa Acocella, Harry Bliss, and Joe Duffy. Do you feel any sort of fraternity with this group? Are you friends with any of them?

DS: Well friends in the way we cartoonists tend to be friends, which is always joyfully see them at events. I have two friends from around that era: Barbara Smaller, who was in the year before me, and Chris Weyant. We’re good friends. Do you consider Matt Diffee in that group?

MM: Well, it’s not me [doing the considering] it’s the chronology. Let me look him up…um, class of 1999, so yeah, close. He was in the group including Alex Gregory and Kim Warp…

DS: A great group, actually.

MM: …Paul Karasik, Michael Shaw. A whole bunch of really good people.

In What’s So Funny? you talk about selling your first drawing to The New Yorker — getting that first O.K. [The Journey To Enlightenment, shown below] and you mention you called your wife first, and then your father, but can you speak a little bit more about it, because the first O.K. for everybody is like this boom! moment…

DS: Absolutely.

MM: …and your life changes. Is there anything else you’d like to say about that moment, or that day, beyond what you have written in the book?

DS: Well I don’t know if it’s beyond, but I was sitting in my studio when a fax came in from Emily Votruba, who was Bob’s [Bob Mankoff] assistant at that time, and I literally couldn’t believe it. I have to say in all honesty, I wept for joy.

MM: Don’t blame you.

DS: I called my wife, and I could barely speak. It was really really exciting. The second person I called, very excited, was my father. My mother had died, so he was living alone by then. He gave me some limited enthusiasm. And as I say in the book, and as you know, just because you sell a cartoon doesn’t mean it’s going to appear the next week. In fact, that cartoon I sold in October of ’97 didn’t appear until July of 1998 — and by then my father had died. As time went on, and I wasn’t in, and I wasn’t in — he’d look in his New Yorker every week — and he finally said to me, “Are you really sure they bought that cartoon?”

MM: It is sad he didn’t get to see it, but he knew it happened. That thing of your work not appearing: they should give out a pamphlet or something of what to expect when you first sell. I know that J.D. Salinger sold a story in 1941, and it didn’t appear for five years [“Slight Rebellion Off Madison” was bought in October of 1941 and not published in The New Yorker until December 21, 1946].

Let’s move more into your book. There aren’t that many [New Yorker] cartoonist memoirs…you’ve done a really good job of tying your being, your life into your work. What I’m saying is: that a lot of times when cartoonists do talks they’ll talk about themselves a little and then they’ll show their cartoons. But you have very nicely woven both your cartoons and your life within your book. Do you think it’s a different approach?

DS: I do. If I can back-up a little. The genesis in some ways of this book were the slide talks I gave where I landed on the idea of introducing myself to the audience for about ten minutes by telling my life story through cartoons.

Below: Speaking At Yale in 2018

One thing I discovered, especially writing this book, is that there’s almost nothing I’ve experienced in my life that I haven’t made a cartoon about at some point. So both in the book, and in talks, it was fairly easy to tell my life story, and pick out cartoons that related to events in my life or choices that I made. What I’m proud of, I have to say, about my book, is I think it’s something unique. There are graphic memoirs, and there are prose memoirs, cartoon memoirs, but I think what I’ve done is meld together truly a prose memoir, but with cartoons, using them at crucial points in the text where they add some enlightenment, but more important, a dash of humor.

One thing I discovered, especially writing this book, is that there’s almost nothing I’ve experienced in my life that I haven’t made a cartoon about at some point. So both in the book, and in talks, it was fairly easy to tell my life story, and pick out cartoons that related to events in my life or choices that I made. What I’m proud of, I have to say, about my book, is I think it’s something unique. There are graphic memoirs, and there are prose memoirs, cartoon memoirs, but I think what I’ve done is meld together truly a prose memoir, but with cartoons, using them at crucial points in the text where they add some enlightenment, but more important, a dash of humor.

MM: And we see there’s a human being behind the cartoon, who’s had a life, and who continues to have a life, of course.

DS: I’m sure you’re this way too, and every cartoonist is to a certain extent this way as I say in the book, the border between my life and my cartoons is very flimsy. Cartooning can be a way of life — it’s the way you are in the world.

MM: In your Yale talk you said, “Captions are like thin filaments. They can be ripped apart by a punctuation mark, or a wrong word, or a rhythm that isn’t quite right.” You know, that to me is like foundational New Yorker thinking. You don’t just write a gag, you’re working on something that really feels right to you.

DS: I agree. Crafting a caption is an art in and of itself. I have to tell you that in writing my book the parts that flowed the most easily, and were actually a joy to write, was anywhere where dialogue was going on. And after awhile I realized, of course I know how to write dialogue — I’ve written 20,000 cartoon captions, and everyone of them is a line of dialogue.

MM: And, as cartoonists we’re putting a lot of editing into every sentence.

DS: Every word. I remember once I handed in a cartoon to Bob [Mankoff]…a cartoon I really loved. It was a Mayan scene of a soccer game. There’s a severed head laying on the ground, and another guy’s holding up a regular soccer ball, and the Mayan guy in charge of the game is saying. “I don’t care if it’s bouncier, it threatens the integrity of the game.” Two things about that: one, that’s an example of what we cartoonists hear — certain phrases in the culture over and over that become like ripe fruits. At that time, everyone was talking, in all the professional sports, about how these new rules were ruining the integrity of the game. But when I handed it in, it was rejected; and then I put it in the next week with the same caption, except instead of saying “bouncier” I said “more bouncy.” And it sold. I realized that “bouncy” is a lot funnier word than “bouncier.” And you learn to pick exactly the right word and where to put it in the sentence.

MM: That’s what we do — we’re word people, really. Many cartoonists are word first...Jack [Ziegler] comes to mind — I believe he spent his time thinking about words first, and then the drawing. I’m all over the place — I don’t have that.

DS: Same with me.

MM: I’ll take whatever comes my way and try to work with it.

DS: What I get asked — as you know as a cartoonist — every time you’re interviewed that same question comes up: which comes first, the drawing or the idea, or the writing? I developed a snarky answer: the egg.

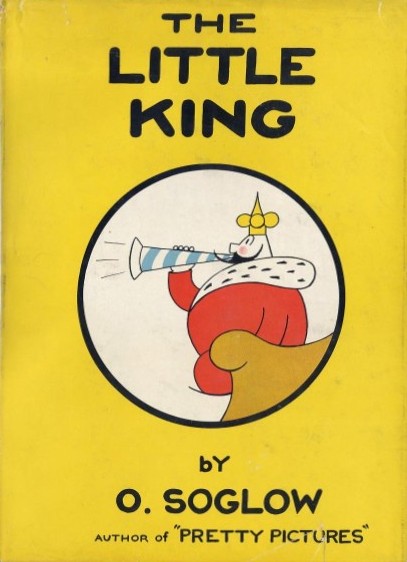

MM: In your book, you say the Little King [the cartoon character created and drawn by Otto Soglow] was your favorite strip. Did anything from The Little King style rub off on your work. I know Soglow’s work, and I know your work, and I’m trying to see some connection. I like finding out if there’s any cartoon DNA in someone’s cartoons from an earlier cartoonist.

DS: I think I say in the book, part of it I think was autobiographical. The Little King reminded me so much of my dad because you never knew what he was thinking. Soglow gave him that wonderful physical form where he was a thing more like a person…impenetrable. All this stuff happens around him and he never changes. And he had a mustache like my father. I made that connection as a kid between the two of them. I always loved him because so much was done without words, and so much depended on the character of that Little King. Who he was was made all the jokes happen. I just really loved him. It was so much more sophisticated, and New Yorkery, than any of the other strip cartoons we’d get…in The Herald Tribune…that had the comics page. At seven years old I didn’t know about sophistication, but I sensed something far more interesting about the strip as a kid.

DS: I think I say in the book, part of it I think was autobiographical. The Little King reminded me so much of my dad because you never knew what he was thinking. Soglow gave him that wonderful physical form where he was a thing more like a person…impenetrable. All this stuff happens around him and he never changes. And he had a mustache like my father. I made that connection as a kid between the two of them. I always loved him because so much was done without words, and so much depended on the character of that Little King. Who he was was made all the jokes happen. I just really loved him. It was so much more sophisticated, and New Yorkery, than any of the other strip cartoons we’d get…in The Herald Tribune…that had the comics page. At seven years old I didn’t know about sophistication, but I sensed something far more interesting about the strip as a kid.

MM: So it was the world — it wasn’t just the graphic that attracted you. It was who he was. Do you still like the Little King?

DS: In preparation for my book I ordered this collection of every Little King Soglow strip, and a bunch of essays about them.

MM: Oh that’s a great book. Every one of us should have a book like that about us, right? [both DS & MM laugh]

This is sort of an out of the blue thought I had the other day: I don’t draw certain things anymore. You’ve been at The New Yorker now several decades. Is there anything you used to draw a lot that you don’t draw anymore? I’ll give you one example: I used to draw a lot of butler drawings. No one does butler drawings anymore.

DS: I can only answer in a general way. As time has gone on I’ve been more and more aware of changes in the magazine and changes in the kinds of things that get bought. And then I think maybe I should avoid this thing I’ve always done; and then I think, no, I’ll just keep being myself, and keep drawing what I’ve always drawn, and they’ll either take it or they won’t.

I don’t draw men with ties anymore. I’d always drawn men with ties in the past, but men don’t wear ties anymore. That’s the one thing that occurs to me. And of course no fedoras [a reference to the first two paragraphs in the May 2, 2004 New York Times piece,“Sex with Einstein? Yes, in The New Yorker”]

MM: I wrote this down while looking through your drawings: your U.S. flags, to me, look like neckties.

MM: I wrote this down while looking through your drawings: your U.S. flags, to me, look like neckties.

DS: I know. I should be more careful in my rendering of them.

MM: No! Why? They’re great.

DS: I love drawing them messy like ties. I don’t know if you remember, but back when Marshall was the assistant [Marshall Hopkins began as an assistant to Bob Mankoff before morphing into a New Yorker cartoonist] they sent around a postcard to all of us with an image of an American flag to indicate exactly how the stripes looked and the stars looked.

MM: Oh my, I never got that.

DS: Maybe they just sent it to me.

[ both laughing]MM: I was fascinated by your use of the hand mirror.

[in What’s So Funny? David explains, “When I was making sculpture, I taught myself to see my pieces clearly by employing a trick I learned from friends who had gone to art school — looking at the reversed image of my pieces in a hand mirror … this ruse always produced instant objectivity, allowing me to spot anything inessential, out of place, or just plain wrong. To this day I do the same with my cartoons”]I never heard of that before.

DS: Really?

MM: And I’m not going to try it because I easily get motion sickness. So you still do that: you hold up a mirror…

DS: I do, because my drawing style and my drawings are not necessarily correct in every way, and I never want them to be. In fact, I like their incorrectness. But I also don’t want the reader to be distracted by some obvious flaw. I don’t want the heads on my people to be so big that someone might look and their first thought might be, well their head is bigger than their entire body. Somehow I can’t see those things all the time looking at them straight on. But for whatever miraculous reason — I don’t understand it myself — when I look at my drawings in a hand mirror anything like that jumps right out at me. Anytime I hand in a finish it’s been through the mirror test.

MM: I looked through all of your New Yorker pieces on the New Yorker’s Cartoon Bank site. I like the way you draw Knights leaving the castle. That’s also one of my things [knights & castles] — I think we both share that.

That tale you tell about you walking with Robert Weber after a cartoonists lunch where he told you he tried drawing like you and realized how difficult it was…is that in the book?

DS: No, that’s in the essay I wrote about Weber for newyorker.com on the occasion of his passing.

MM: Oh yeah, I really liked that. I have to say, after looking at all your work, I’m surprised there was any problem there at the cartoonists lunch table [referenced in David’s Robert Weber appreciation] about how well you drew.

DS: I never tried to “draw well” I always wanted my drawings to have a direct feel, in the sense that I thought up the idea and then I drew it — I didn’t fuss about it too much. So I wasn’t surprised [about some of the lunch table grumblings]. I love my drawings, but they’re an acquired taste I think because they didn’t, at the time, look like anyone else’s at The New Yorker.

One of the first [New Yorker] parties I went to, I think it was at Bryant Park — a really fun event — I was having a really good time. I was standing with Andy Friedman [Andy was an assistant in the cartoon department. As with Marshall Hopkins, he also began contributing cartoons to the magazine…sometimes under the name “Larry Hat”] and at some point one of the veteran cartoonists came up to me and said, “I know who you are.” And I thought, “Oh great! He knows who I am.” And then he said, “You don’t belong in The New Yorker. What do you draw with: a stick?” I was hurt, and I was angry. He turned and walked away. I wanted to say, “Just because I don’t draw like you doesn’t mean my drawings aren’t good.” But I was so stunned I couldn’t say anything. And then Andy put his arm around me and said, “Now you know you’re doing a really good job because you’re making people angry.” I literally went home and sat down and drew that drawing of the supposedly well-drawn guy and the awkwardly drawn dog. When the [New Yorker’s] Cartoon Issue came out in 2004, that was the first cartoon in the issue. I was so happy about that.

MM: That’s great. And that is one of your classic drawings.

DS: We sometimes do a cartoon that fills a hole in us, and that one really really was a satisfying experience.

MM: It would be fun to hear from you who you ran into in your earlier days who it was exciting for you to meet. Bob Weber, I’m sure, is on that list. But are there others that you’d see when you went into the office, like Sam, and say to yourself, “Oh my god — it’s Sam Gross.”

DS: Well let me tell you that in 1972 or 73, I had a problem in that I had done some cartoons and had sent them to Penthouse Magazine, and they appeared in Penthouse — two of them — without my name, without any signature, any payment. I didn’t know what to do, and someone suggested I should come down to New York and meet with people from the Cartoon Association [a professional organization formed by cartoonists. It no longer exists] of which Sam [Gross] was a big macher in that.

Sam helped me out a lot, and he was really kind, and gave me really good advice, and got me my money for the cartoons. But in the course of that visit I was invited to a gag session that was in some office in midtown, way up high. There was a room with about ten guys there. Somebody sat up front at a kind of lectern with a couple of phone books. Everyone else sat there with their pens and pads of paper ready. And the person in charge would read arbitrary things from the phone book like “mover,” “lawyer,” “swimming pool.” And then everybody would madly draw cartoons putting those things together. They called it a gag session.

And that’s when I had a really great experience with Sam who was a real hero of mine, and still is. Because I think Sam is the funniest cartoonist that’s ever been.

At one point, I said to Sam, “I’m trying so hard, I can’t sell to The New Yorker — I don’t know if this is the right thing for me to do.” and Sam said, [here David does a very good impression of Sam Gross speaking — something almost every cartoonist will automatically do when remembering something Sam has said to them] “You wanna be an insect? You wanna do what someone else wants you to do? C’mon, you’re a cartoonist. It’s the best thing in the world — just stick with it. Don’t get discouraged.”

I can’t explain it exactly, but having Sam give me that vote of confidence was just amazing because I so revered Sam.

MM: The gruff pat on the back.

DS: He was just great. And meeting Arnie Levin was a thrill for me. I met Arnie when I first started at the magazine — he was so kind and so supportive, and I so loved his work. That meant a lot to me.

And then I did a series of interviews (Victoria Roberts was the founder of it, but she didn’t want to do the interviews). I met everybody. I met Gahan [Wilson], who was amazing. A sweet sweet guy. My wife and I actually visited him in Sag Harbor at one point, at his crazy house. As you can imagine he had all this creepy stuff around his house. I interviewed George Booth — an amazing experience, a delightful challenge, because George would never give me a straight answer. He’d wander off and tell a story that was so much better than a straight answer. The audience was so entertained — it was really great.

MM: Were those interviews taped?

DS: No, no they weren’t. It was pretty primitive.

MM: Too bad.

DS: I interviewed Roz [Chast] and Barbara Smaller. I interviewed Lee [Lorenz], which was really interesting. I found out that Lee had been a close friend of my favorite artist, Philip Guston, and the best man at his wedding. I collect his work. That just blew me away when I found that out.

MM: I looked up Philip Guston after you reading your book — or after listening to your Yale talk — whichever one you mentioned Guston, and I saw all those Nixon drawings he did.

DS: Fabulous fabulous stuff.

MM: I could see some sort of connection there, why you would enjoy that work, style-wise, and otherwise.

— (End of Part I. In Part II, to be posted tomorrow, David and I will discuss a number of his New Yorker cartoons)

Publishing History of Drawings Shown Above (all by David Sipress, except *)

“I just wish I could loosen up like you.” The New Yorker, January 12, 2015.

*By Arnie Levin: “Run for your lives! The Lord of the Dance is coming” The New Yorker, August 3, 1998.

“Are we there yet?” The New Yorker, July 6, 1998.

“I don’t care if it’s more bouncy — it threatens the integrity of the game.” The New Yorker, December 24, 2012.

“Bad drawing!” The New Yorker, November 9, 2004.

“I ran out of room.” The New Yorker, September 11, 2006.