David Sipress: The Ink Spill Interview, Part 2

In Part 2 of my interview with New Yorker cartoonist, David Sipress, whose book, What’s So Funny?: A Cartoonist’s Memoir will be out March 8th, we talk about a dozen or so of David’s New Yorker drawings: where they sprang from, what he was thinking about them at the time they developed, and all kinds of other things. David selected a handful of drawings he wanted to talk about, and I selected a handful of his I wanted him to talk about.

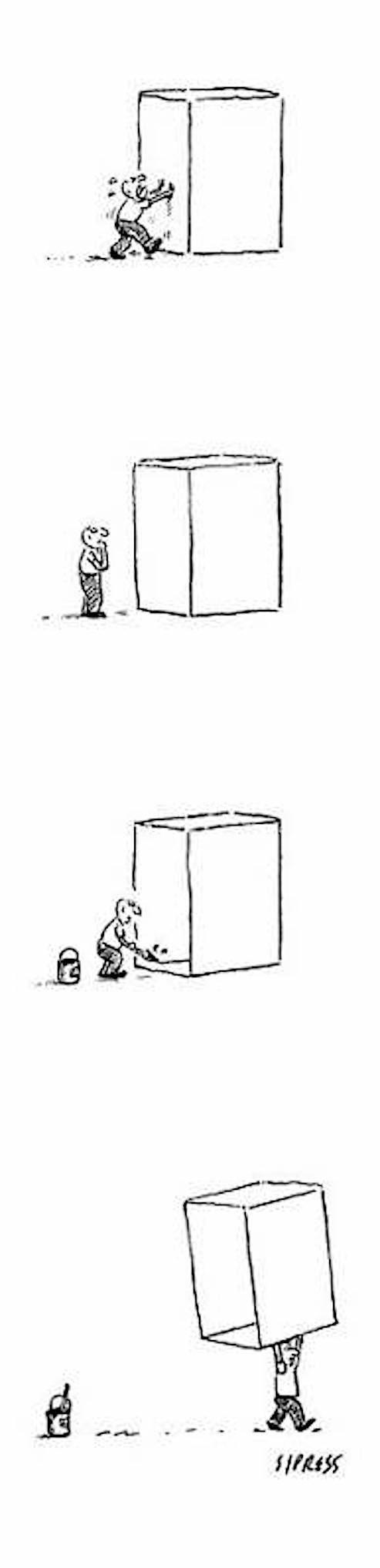

We began with this drawing, published in The New Yorker, March 14, 2016.

Michael Maslin: I’m looking at your list — the four-part box drawing. That you picked that out is so interesting. Can you talk about why.

David Sipress: That drawing is really important to me. The first time I drew it I was much younger; I submitted it every year, twice a year, for fifteen, sixteen years, because it connected my training as an artist and my training as a cartoonist. It’s this magical thing that a single line can do, that I learned, when I learned life drawing — the sort of serious drawing that I got into. It’s kind of like a magic trick, that cartoon.

It also spoke to me about overcoming obstacles. I’ve always thought of it as a cartoon that’s a metaphor for finding difficulties in life and finding a solution. Funnily enough, I got a lot of that in response to it. [people would ask] “Is this a political cartoon?” because it came out during the Trump Administration.

MM: They’re all political right? All our cartoons are political.

DS: Yes. And also it kind of goes back, now that I’m thinking about it, to The Little King stuff. So much happened in those sequential Little King cartoons that required no words at all. And also, like a magic trick at the end — the punchline.

MM: I’m looking at it now, and I can actually see the Little King doing this, being this guy. It’s pretty funny.

When you were a little kid did you enjoy that MAD Magazine three prong thing that turned into two prongs? It was a visual trick on your eyes.

MM: I used to draw that thing over and over again. I made myself understand how to draw it.

DS: I’d completely forgot about that. You’re absolutely right — I loved that.

MM: Still to this day, I look at and wonder what is going on.

DS: I hope I’ve answered your question about that drawing [the 4 part box drawing]. Some of the reasons I love it, I can’t even express. And here’s the thing: when I sold it, I got a note from Bob [Mankoff] — the only note I ever got from Bob in all those years, and he said something like, “Ok, finally, you win.”

MM: I had something like that with Lee [Lorenz]. I kept sending in a drawing I’d decided they really needed to buy. Finally Lee said to me — he hardly ever said anything to me — he said, “Stop sending in this drawing.” He had had it with that cartoon.

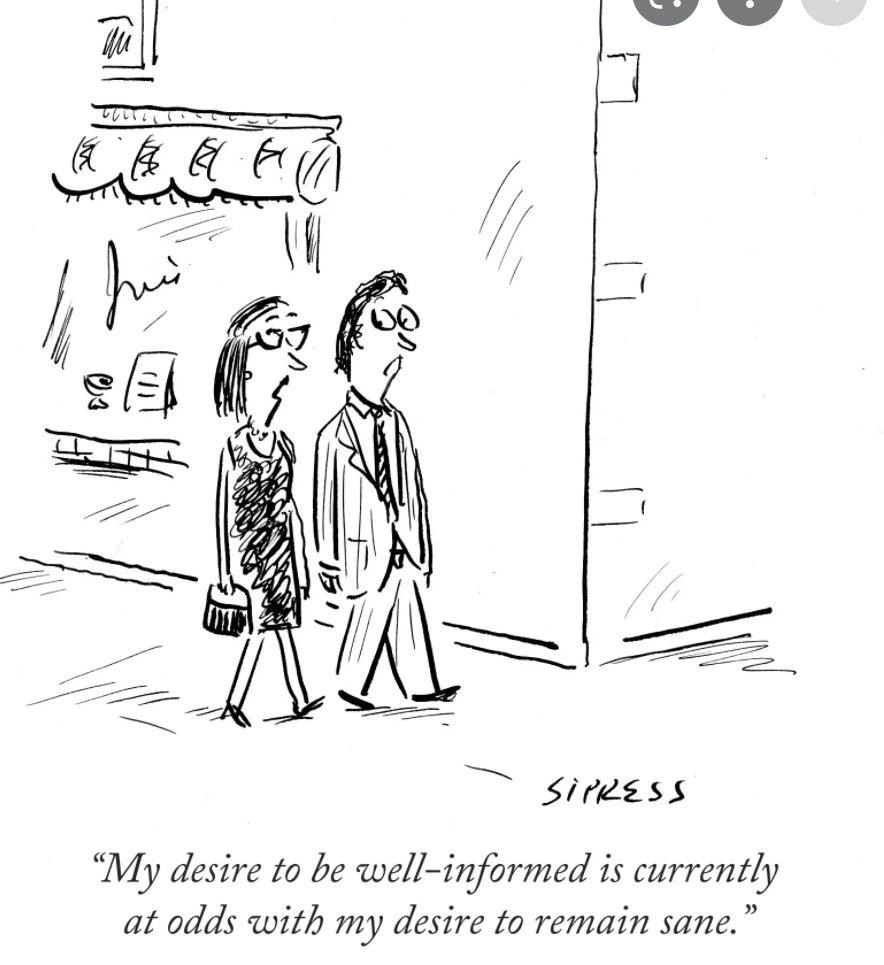

Your “well- informed” drawing is, you have said, your most popular drawing, yes?

DS: It’s by far. It’s been copied, reprinted, shared — all that stuff, ever since it came out. And every time the world gets in a difficult place, it once again rises on the internet, and I get thousands of “likes” for it. I’m very proud of that cartoon. It wasn’t in The New Yorker — they rejected it. I don’t remember where I first published it…Funny Times, or somewhere else. I think what that cartoon shows, something that is really interesting to me, which is that you can do political stuff without focussing on making fun of or saying something trenchant about something in politics and pointing a finger. Sometimes a really successful cartoon — not just a political cartoon — is one where you express a feeling that connects with your audience. And part of the humor — in that case the only humor in that cartoon — is people saying, “Wow, that’s exactly the way I feel.”

MM: Right. It’s what I think of as a very successful New Yorker cartoon — one that makes you think beyond.

DS: People respond really well to that. It’s one of the many things I’ve learned about cartoons, and it’s such a pleasure — and I talk about it in the book — how when I was a kid, if you make jokes about your own experience, and your own feelings, and you trust that if you put them out in the world it’s going to make a connection, that is a really wonderful thing to figure out because you don’t have to struggle so much. As I’ve said before, there’s nothing in my life I haven’t made a cartoon about. And I very rarely think, oh, let’s come up with a funny idea.

MM: Did you ever have a period…I know there are cartoonists that do this: they construct cartoons. I know you draw from your life — you’ve written that, and you’ve just said it here, but there are cartoonists who sit at their desks and cobble together ideas. I had a short period of that when I got into the magazine. I didn’t know what I was doing — I’d go through the thesaurus. Did you ever have that kind of time in your life?

DS: On and off I go to that place if I’m having a hard time, especially thinking up a cartoon. But here’s the thing, you can even cobble together a cartoon like that and inevitably, in the end, I think it does reflect who you are and your experience. I really think that. So I don’t think there’s that much of a distinction between the two.

MM: So you’re saying the ingredients can come from anywhere but as the chef…

DS: You are who you are as an artist, and that’s going to leak into everything you do.

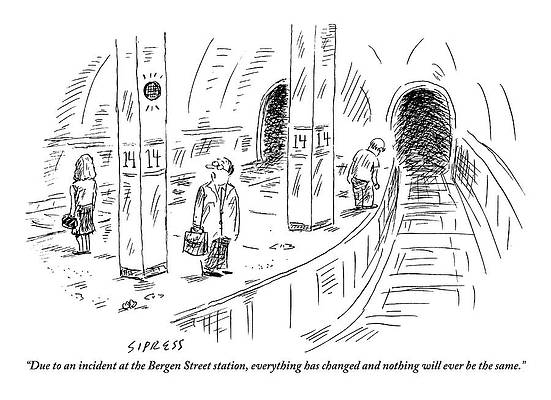

MM: How about the Bergen Street Station drawing.

DS: That’s another of my great favorites that I’ve done.

MM: I looked up Bergen Street by the way, wondering if it was a real place. I don’t know anything about Brooklyn.

DS: Oh it’s a real place…my agent lives on Bergen Street [laughs]. It’s a real street — it’s not very far from me. It’s an example of what we were talking about before, in caption writing. If I had said “14th Street,” or “Grand Central Station,” or something like that, it wouldn’t be quite as funny, but “Bergen” is, in itself, kind’ve a funny word.

MM: It is funny — that’s why I looked it up. I thought, oh maybe he made this up.

DS: My Yiddisher Grandmother used to pronounce it, “Boy-gan.”

MM: Maybe that is the way to pronounce it.

DS: I live very close to Bergen Street, and I know that station well, and it was in that station that I thought of the cartoon. I thought it up right after 9/11, during the whole 9/11 ethos, when going down into the subway still felt scary. There was some kind of announcement on the loudspeaker, and that cartoon just popped into my head — y’know, that magical thing that happens once in a blue moon. It just popped into my head, fully formed, and ready to go.

MM: Isn’t that the best when that happens.

DS: It’s a thrill.

MM: You just have to remember to write it down.

DS: I was a little younger then, so I was much better at remembering.

MM: Have you ever had that moment — I’m sure you have — when you think of something, and for whatever reason — you’re driving or something — you can’t write it down?

DS: Have you ever thought of cartoons in your dreams?

MM: Yeah. Bad ones.

DS: Those get lost very easily. But then, years later, something might remind you of it. I have really learned to write everything down at this point.

MM: Does the Bergen Street Station look like that?

DS: No, actually I based it on the 14th Street station. I don’t know why — but maybe because I’m more familiar with it. Well, maybe not more familiar with — I almost always draw the 14th Street station when I draw subway stations, for some reason. Bergen Street I still go to a lot because there’s a wonderful food shop, called The Bklyn Larder, which is right by Bergen Street and Flatbush Avenue.

MM: It’s difficult to draw something like that. Charles Addams did it. I did a subway drawing that ended up as a caption contest drawing — that was a challenge just remembering what things look like.

DS: I liked drawing the dark tunnel in the distance, because you could crosshatch forever.

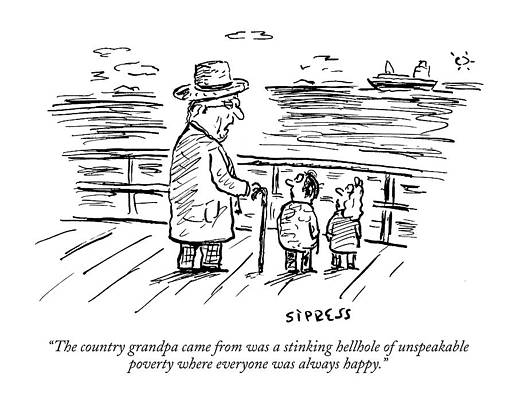

MM: Now the “sinking hell hole”…I loved the response to that at your Yale talk. Isn’t it great to hear people laughing?

DS: The best, yeah.

MM: Something we don’t get to hear, but we know what we signed-up for…

DS: I guess.

MM: Can you talk about the stinking hell hole…and the use of “stinking.”

DS: That [drawing] encapsulates my experience as the son of an immigrant. Because my father — it’s in the book — gives two versions of the past, and he didn’t give much information about it, one way or the other. One version, mostly articulated by his silence, is that it was really horrible, awful, and difficult. But at the same time there’s a sort of nostalgia, a longing for what that life was like. So that cartoon is about that ambiguity. I’m very very proud of the caption because every single word seems to me like the perfect choice. And the rhythm of it — it has that kicker at the end that’s so precious to us caption writers. [Reads the caption]…that really expresses my confusion about the past that my father was so secretive about. I could never figure it out. So it’s a very intensely personal cartoon.

MM: I think you and I share this: I hear captions. I would never send a caption out that did not feel right: the rhythm of it, the whole thing — it just has to be right.

DS: Exactly.

MM: In your mind where are they standing in the cartoon?

DS: They’re standing near the Brooklyn Bridge looking across the East River to Manhattan.

MM: Is that the promenade?

DS: Now it’s called Brooklyn Bridge Park. I don’t think Brooklyn Bridge Park existed when I drew that cartoon. It’s probably — yeah, it’s the promenade, I’m sure.

MM: How long ago did you move there [to Brooklyn]?

DS: I’ve been living in Brooklyn since ’89.

MM: I love the “…who’s going to finish your sentences?” drawing. There are so many of these things we do, where we use domestic situations, and I’m always thrilled when someone does something different with it. And, obviously, it’s funny. Anything to say about that drawing?

DS: That’s one of a whole school of my cartoons that is based on my marriage. It’s another one of those things I put out there because it’s my experience, and people will connect to it. My wife did at some point get really irritated that I would never let her finish a sentence, and that’s where that one came from. It’s another example of something I like to talk about. In the book I talk about something I call my cartoon brain. Which is this part of my mind — I’m sure you have the same thing — there are very few situations when some part of me isn’t thinking about whether or not there’s a cartoon in this. That can happen in really inappropriate situations. In my book I write about it as a kind of compulsion, and I compare it to my father who had his own compulsion, which was to bargain, in every situation he was ever in in life. And mine turned out to be thinking up cartoons at times. My father’s bargaining got him into a little bit of trouble. It would often happen when it wasn’t appropriate.

Another example of one of my cartoons is the one with the husband saying to his wife, “Well, if it doesn’t matter who’s right and who’s wrong, why don’t I be right and you be wrong?”

That’s probably the second most popular cartoon I’ve ever done. And that’s an example of inappropriate cartoon brain activity. My wife, Ginny, trained as a lawyer; issues of right and wrong are really important to her. She’d always bring up in any of our fights, “The only thing that matters to you is being right.” So we were having this fierce argument once, and she said that, and she noticed my eyes widen, and she said, “You’d better not be thinking of a cartoon.” About a month later that cartoon appeared in the magazine.

MM: I remember the laughter from that one at your Yale talk.

DS: Yeah, people love that one, and can really identify with it.

MM: These are evergreens, these drawings — ones that are funny now, would’ve been funny in 1935, and will be funny fifty years from now.

…So, let’s turn to your “quitting school” drawing.

DS: That is ripped from life. I was so pleased when I thought of that cartoon, and it found its place in my book very easily.

MM: I wrote down something [I found in your book] that led to your decision to become a cartoonist. You said you were “trapped in the wrong life” which I found very interesting.

DS: That particular moment I was in graduate school studying in the Department of Soviet Studies at Harvard very much knowing deep down that it was a mistake. It was a choice I had made to please my father, and also a choice I had made to avoid the draft. I had to be in grad school. At the end of a semester there was a party; there were about eleven of us, first year, in the department. And at the party there was a lot of Boone’s Farm and marijuana and stuff…

MM: Sorry to interrupt…what’s Boone’s Farm?

DS: Boone’s Farm is the cheap wine that we hippies drank back in the 60s.

At some point people in my department started unveiling who they really were. At least half of them were in the Department of Soviet Studies because they were being sent there by the government. They were in training as spies or whatever. And that’s not who I was. When I walked home that night that’s when I had the thought I was trapped in the wrong life. And it was one of the things that pushed me to leave that life not so long afterwards.

MM: I’m glad you realized that.

MM: I’m glad you realized that.

DS: Me too. It wasn’t easy. I had to push back against a father who I desperately wanted to please. I had to make a decision about my own future.

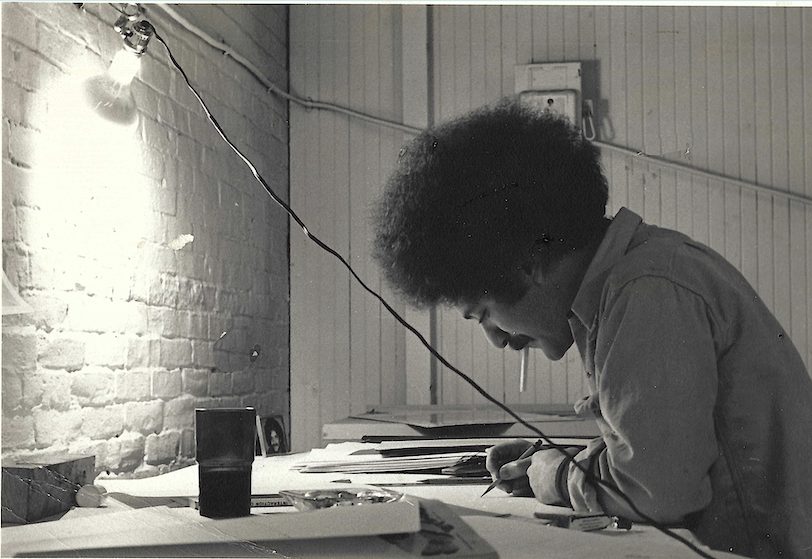

— Left: at work in the 1970s

MM: When I think about your book, several things really stuck with me. The robbery stuck with me [there’s a chapter, “Robbery,” in What’s So Funny? ] but also the phone call, when you called your parents to tell them you weren’t going to be in college anymore. It stuck with me because I was imagining what an unbelievable moment it was for you, and for them. We will of course, encourage readers to go to the book to read more about this, because something good did happen…

DS: Yes, something good did happen.

MM: This drawing, “By the way, great mascot” — another grand drawing that turned out really well, and of course the mascots are just…Do you have any recall of that drawing coming together?

DS: Absolutely. First of all there’s an amazing [Eldon] Dedini drawing of two armies facing off against each other which inspired me a lot. It’s a famous cartoon.

–– Eldon Dedini’s drawing appeared in The New Yorker, January 14, 1991

My wife graduated from The University of Alabama and went on to Harvard Law School. She still has a certain attachment to the University of Alabama, and very much an attachment to Alabama football, which is, believe it or not, something we watch religiously. We were invited to see my very first college football game, Alabama against Tennessee — this was about three or four years ago. I was excited about seeing an in-person huge college football game with a hundred thousand in the stands. It was a really remarkable experience…I noticed the mascots; they were just funny…sitting there I thought of that cartoon. I’ve done a number of these in the past: I mush together sports and warfare, because I do think they’re similar. There are six or seven I’ve done making that connection.

MM: I looked up your history of appearances in the magazine. In 1998 you had 3 drawings, in 1999 you had 18 drawings, and then you exploded in the magazine. Any particular reason you think that happened? You confidence level increasing? Or Bob [Mankoff] just fell head over heels for your work?

DS: Definitely my confidence got better. Bob was really proud that he had brought me on, and had a lot of confidence in me. More than that, I can’t explain it. The ups and downs of how many you sell depend on a lot of factors beyond your control.

MM: Your Running Of The Brie drawing, it’s one of your most masterful graphic displays [speaking with David, I likened it to this Michael Crawford drawing]. When you look through all your drawings there’s a certain look, and then every once in a while there’s an explosive graphic. I thought this one, in particular, was different for you — that’s why I chose it for us to look at. Was that fun for you to do?

DS: For many years I would reject an idea like that because I thought it’s too complicated — I can’t draw that. First of all, the thing about that cartoon that’s special is that that is the very first one I sold to Emma Allen [the current New Yorker cartoon editor]. By 2017 I had become more confident as an artist, and I was no longer rejecting Ideas I thought were too complicated for me to draw. And I began to have fun with it; I had a lot of fun with that drawing. It took me a really long time to get it right. A lot of looking in the hand mirror. I just loved the idea so much I just told myself you gotta go through this. It took me days to make that drawing. But it was really fun, because the flags, the melting cheese, the expressions on the people getting stuck in the cheese and stuff, it was just a lot of fun to draw. I wanted to create that steep French town street I was familiar with from my travels.

MM: I’m looking at it now. It’s great. Did they run it a good size?

DS: Yeah, it was a pretty good size — I was pleased about it. Y’know, it’s another one of those ideas that just pop into your head. I was thinking about the running of the bulls when I was in a cheese store. That’s where that came from.

____________________________________________________________________

David Sipress’s Website (includes links to various videos of interest).

Link to David Sipress’s New Yorker cartoons on the magazine’s Cartoon Bank site.

A Selected Bibliography

What’s so Funny?: A Cartoonist’s Memoir (Mariner, 2022)

It’s A Teacher’s Life (Plume, 1993)

It’s Still A Mom’s Life (Plume, 1993)

It’s A Cat’s Life (Plume, 1992)

Sex, Love, And Other Problems (Plume, 1991)

The Secret Life Of Dogs (Plume, 1990)

It’s A Dad’s Life (Plume, 1989)

It’s A Mom’s Life (Plume, 1988)

Wishful Thinking (Harpercollins, 1987)

Is It Really Only Monday: Cartoon Book (Pitman, 1981)

Further Reading:

A Case for Pencils, November 17, 2015

Publishing Dates of Drawings Shown Above (all by David Sipress, except as noted by *)

uncaptioned: man carries box The New Yorker, March 14, 2016.

“My desire to be well-informed is currently at odds with my desire to remain sane.” Publication uncertain. c. 2015-2016.

“Due to an incident at the Bergen Street station, everything has changed and nothing will ever be the same.” The New Yorker, August 1, 2011.

“The country Grandpa came from was a stinking hellhole of unspeakable poverty where everyone was always happy.” The New Yorker, January 24, 2000.

“Well, if it doesn’t matter who’s right and who’s wrong, why don’t I be right and you be wrong?” The New Yorker, October 30, 2000.

“You’re quitting school? After everything we sacrificed for you.” The New Yorker, January 29, 2018.

“By the way, great mascot.” The New Yorker,

* Eldon Dedini: “My people will get back to your people.” The New Yorker, January 14, 1991.

The Running Of The Brie The New Yorker, May 7, 2018.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Happy 93rd Birthday, Arnold Roth!

The Spill wishes the great cartoonist, Arnold Roth all the best!

Back in 2016, I had a great time talking to Arnie Roth about his work on John Updike’s Beck book cover art. You can read that piece here.

Mr. Roth’s Spill A-Z entry:

Arnold Roth Born, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, February 25, 1929. New Yorker work: November 16, 1992 –. Mr. Roth’s career is long and storied, his work associated with a number of magazines including Playboy, Esquire, TIME, and Punch. Read all about it on his website: arnoldroth.com

_________________________________________________________________

The Spill is pleased to post this lovely Bill Woodman tribute by Misha Gross, the daughter of Sam Gross.

Misha Gross Remembers Bill Woodman

Bill Woodman was generally a man of few words, a quiet, unassuming guy. He would make up stories about how he had lost half of one of his fingers. He would often shove the rest of the finger up his nose so that it looked like the whole thing was up there. I never tired of his wacky stories about various subjects such as growing up in Maine, or his stint in the Navy and why he didn’t end up with a lousy tattoo souvenir of his service.

From my birth, or perhaps even before that, Bill was a frequent visitor at our home. Pretty much every other week, Bill and Sam would sit at opposite sides of the dining room table and draw. Sometimes, for hours at a time, nary a word passed between them, not even a glance. Occasionally, one of them would pass over to the other a gag for criticism, but otherwise they only truly began to acknowledge each other’s existence in the late afternoon or early evening, over a Jack Daniel’s or two (or three or four, depending on the mood).

Bill was not only an astute cartoonist but also an excellent watercolorist. We are fortunate enough to have a few of his plein air paintings hanging on the walls. I will be reminded of the character and talent that is Bill every time I think of my childhood in that apartment and look at them. He is and will remain among the elite cartoonists who for numerous decades have left their indelible mark on the readers of not only The New Yorker, National Lampoon, and Playboy, but countless other publications. Billy, we will really miss you.