Do Numbers Matter?

I’m not good with numbers, but I do enjoy numbering. For instance: I keep track of new New Yorker cartoonists as they enter the fold; I have a year-by-year list of who was published, and when their first drawing appeared in the magazine. It gives me some kind of anchoring satisfaction to glance at the list and see that, say, Edward Koren and Donald Reilly began at The New Yorker in the same year, and that they were the only cartoonists brought in that year. (I mentioned to Edward Koren the other day that his sole classmate was Donald Reilly. Ed said that he was surprised that he and Donald came in the same year: “I thought he was older — I didn’t think he was in my specific time”).

I’m not good with numbers, but I do enjoy numbering. For instance: I keep track of new New Yorker cartoonists as they enter the fold; I have a year-by-year list of who was published, and when their first drawing appeared in the magazine. It gives me some kind of anchoring satisfaction to glance at the list and see that, say, Edward Koren and Donald Reilly began at The New Yorker in the same year, and that they were the only cartoonists brought in that year. (I mentioned to Edward Koren the other day that his sole classmate was Donald Reilly. Ed said that he was surprised that he and Donald came in the same year: “I thought he was older — I didn’t think he was in my specific time”).

Another list I keep tells me approximately how many cartoons a good many of the contributors have published (at present, the list contains those who have contributed 100 or more). What the list doesn’t tell me is how many cartoons contributors have sold. I used to have a running conversation (I suppose it was more of a disagreement) with a colleague about which was the more “important” number: number of drawings sold, or number of drawings published. I was in the number of drawings sold category — the number of bought drawings “on the bank” (the term used by the magazine to describe bought work not yet published) is a far smaller pool than the ocean of work submitted yearly for consideration. In other words: it’s more difficult to sell a drawing than it is for an already bought drawing to be published. Thus (in my figurin’), “number of bought” outweighs “number of published” in importance.

A fascinating side bar to the list is what the numbers of published drawings meant (or means) when letting the mind wander through the pantheon of New Yorker cartoonists. On the one hand there is William Steig, at the very top of the list with over 2,000 published drawings*, and at the other end is Mary Petty, whose total is 219**. Both are cartoon gods — does it matter how many cartoons they published? Looking at lists of numbers (I won’t post the list — I’ve learned there is sometimes a great deal of sensitivity about one’s number of cartoons published), and thinking about these two artists in particular, I think the answer is both a yes and a no.

Of course it mattered/matters financially to the artists. And, I would guess, it mattered/matters to them how often their work was/is appearing. For a cartoonist, there is nothing quite like selling a drawing to The New Yorker, but there is also nothing quite like seeing your work published in the magazine.

Mary Petty’s body of work is incredible — no matter how few or how many of her drawings were published. Sure, it would’ve been great to see more of her work, but what work of hers there is to enjoy is not somehow diminished because there is so much less of it than Steig’s. I’m just thankful she came along.

*That number does not include Steig’s approx 125 covers.

**Mary Petty’s # of 219 does not include her 38 covers.

From the Spill‘s A-Z:

Mary Petty Born, Hampton, New Jersey, April 29, 1899. Died, Paramus, New Jersey, March, 1976. NYer work: October 22,1927 – March 19,1966. Collection: This Petty Place ( Knopf, 1945) with a Preface by James Thurber.

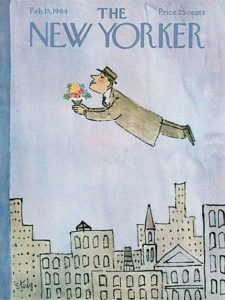

William Steig Born in Brooklyn, NY, Nov. 14, 1907, died in Boston, Mass., Oct. 3, 2003. In a New Yorker career that lasted well over half a century and a publishing history that contains more than a cart load of books, both children’s and otherwise, it’s impossible to sum up Steig’s influence here on Ink Spill. He was among the giants of the New Yorker cartoon world, along with James Thurber, Saul Steinberg, Charles Addams, Helen Hokinson and Peter Arno. Lee Lorenz’s World of William Steig (Artisan, 1998) is an excellent way to begin exploring Steig’s life and work. NYer work: 1930 -2003.