A note to visitors: Due to an overload of traffic, the Spill was down for much of yesterday. I’m leaving the below piece by Linda Davis up on top today as I don’t believe it got its fair share of the spotlight. Newer posts follow the Addams Love Letters piece.

Addams In Love: Letters From A Young Cartoonist

Yesterday was pub day for the new edition of Linda H. Davis’s Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life (Turner) — a must read for every fan of Addams’s work, New Yorker art, and New Yorker artists.

Yesterday was pub day for the new edition of Linda H. Davis’s Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life (Turner) — a must read for every fan of Addams’s work, New Yorker art, and New Yorker artists.

To celebrate the release of this new edition, Ink Spill is fortunate indeed to have Ms. Davis’s “Addams In Love: Letters From A Young Cartoonist” make its debut here. What a treat to have Ms. Davis discuss this array of previously unpublished illustrated letters by the great New Yorker artist.

My thanks to Ms. Davis, and to the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation for permission to reprint the letters.

Addams In Love: Letters From A Young Cartoonist

by Linda H. Davis

Fifteen years after the first publication of my Charles Addams biography, and on the eve of a new publication, a treasure has come my way: 15 love letters, deliciously written and buoyantly illustrated by a 23-year-old Addams.

Imagine my relief that nothing in them contradicts what I learned over the course of 6 years, as I slaved away, studying cartoon after cartoon (for which no one, including me, pitied me) with the full cooperation of Addams’s widow and intimates. But these letters do add to the picture, particularly of the cartoonist’s early years, when his career was starting to take off.

In 1935, Addams –always “Charlie” to his friends—was in love with a hometown girl, 22-year-old Jewell Valentine Bunnell. She was beautiful, bright, creative, and fun-loving – “I think the fondness we have in common for cemeteries is one of the many reasons I love you,” Charlie wrote. She was attending Beaver College (later, Arcadia University) outside Philadelphia; Addams was a college drop-out living at home in Westfield, New Jersey, with his widowed mother. Employed full-time by True Detective, the “gathering place of geniuses,” he joked, where he lightened the blood stains in crime scene photos to render them a bit more palatable for publication, and drew Xs to mark the spot where the body was found, he had boldly decided, in the midst of the Great Depression, to quit his job and make his way as a cartoonist.

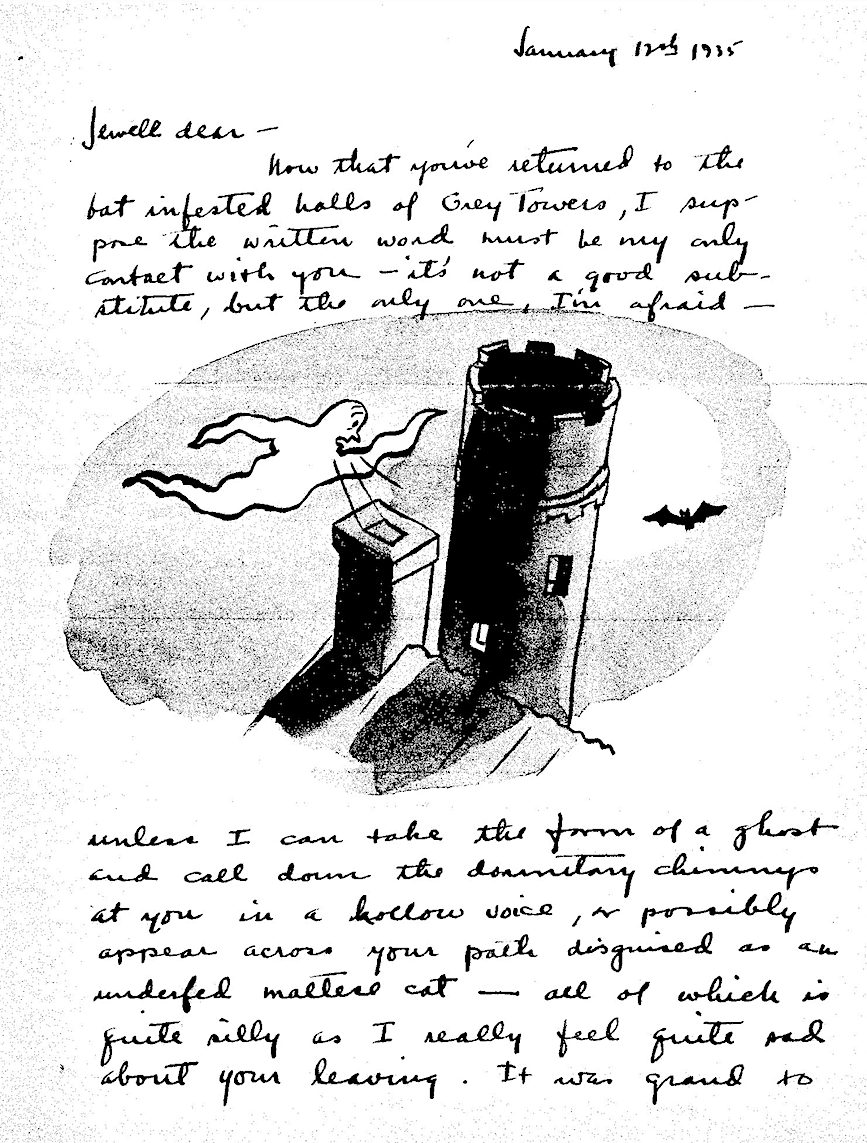

“Jewell dear,” he wrote in his pleasing handwriting on January 12th. “Now that you’ve returned to the bat infested halls of Grey Towers, I suppose the written word must be my only contact with you—it’s not a good substitute, but the only one, I’m afraid [,] unless I can take the form of a ghost and call down the dormitory chimneys at you in a hollow voice, or possibly appear across your path disguised as an underfed maltese cat….” And he drew her a picture:

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

By January of 1935, when his letters to Jewell begin, he had published only 6 cartoons in The New Yorker. But he had reason to be hopeful. The New Yorker editors were encouraging him and feeding him ideas. (From the beginning, Addams took their criticisms and requests for changes like a pro—going to “the sub-basement” of The New York Times to study the printing presses, to the police department to be fingerprinted so he could draw it.) He documented his total income that month as $75.00 – $15.00 more than he had been earning at True Detective. (The minimum wage in the United States then was $12.00-$15.00 a week.) The next month it jumped to $145.00, and he soon got a $5.00 raise per drawing.

As a suitor, Addams—whose later romances included Jackie Kennedy and Joan Fontaine – was already the most charming of men. His letters to Jewell were characteristic of the letters he wrote later: playful, sharing, generous, and romantic.

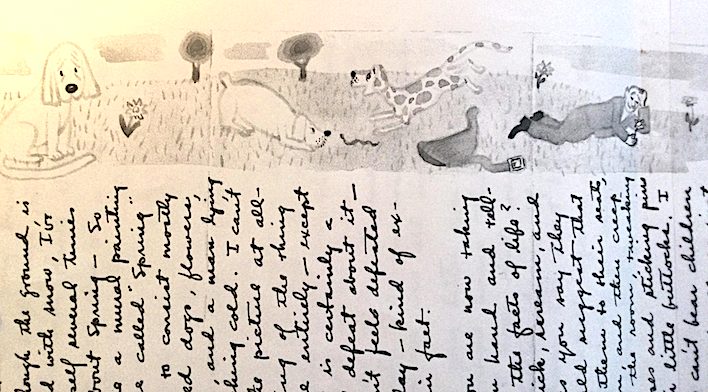

But he was serious, though modest, about his art. His “favorite” artist was Thurber, he told Jewell, and sent her a little “mural” tribute to Thurber’s hounds of spring on winter’s traces:

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

He thought in pictures. Everything, it seemed, suggested a drawing. And if nothing interesting was happening, he invented a story. A sampling:

When Jewell sent him a pretzel, he said he resisted the temptation to eat it. “Instead I brought out my paints and gave it a coat of gilt paint and put it in my hope chest where it shall remain evermore.” And he drew her a picture:

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

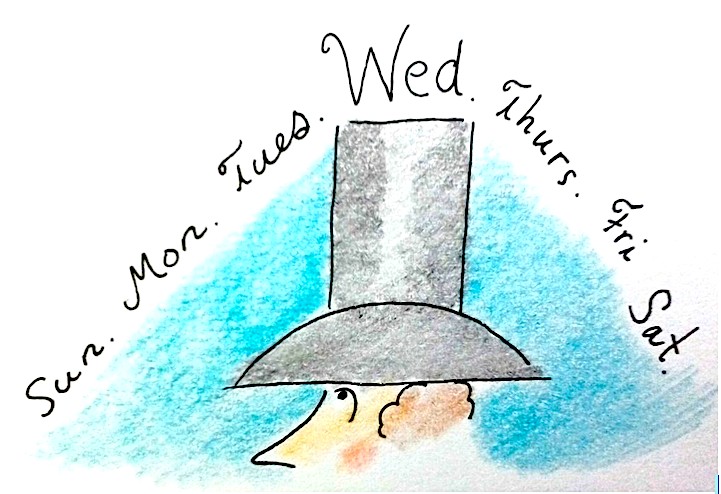

He encouraged her to have fun.

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

He regaled her with stories. After an insect bit his face and half closed one eye, he was startled “speechless” when he looked in the mirror:

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

Bored to unconsciousness in a hot room by a man who droned on for a full half hour about his trip to Florida, Addams had literally fainted. “I heard people saying, ‘It’s Charlie Addams’ and I remember mumbling softly to myself, ‘I’m dead, I’m dead….”

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

Forced to cook his own lunch one day, he had decided to “grow a goatee and all, and if I can get a bit more on the chubby side,” become a chef:

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

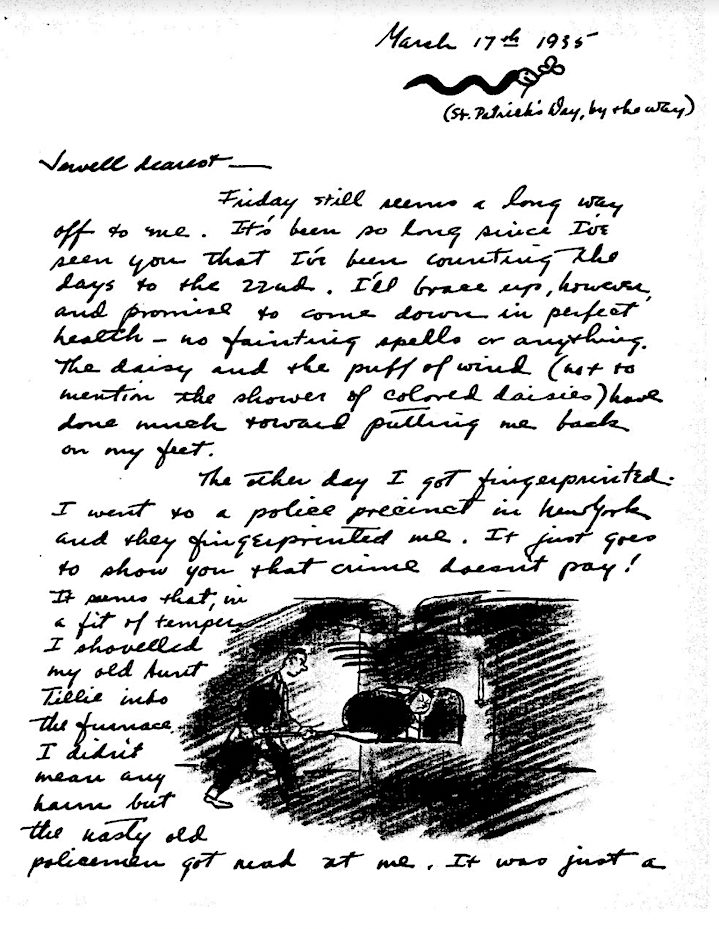

Oh, and about that day he went to the police station to get fingerprinted in order to draw it, he confessed the true story: he had been caught shoveling his “old Aunt Tillie into the furnace.”’

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

His plan was to try to sell one or two drawings a week– preferably to The New Yorker. But from the beginning, he struggled to come up with ideas. “I’m faintly worried about the whole thing,” he confided to Jewell. “But I’ll be light-hearted about it and go around with a fixed grin on my face until someone shoots me in desperation.”

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

After a wasted week “in quest of ideas,” and missing Jewell at faraway Beaver College, it suddenly came to him: Beavers. “I began to feel that beavers were following me around and jumping out on me from surprising places. The fact that I think so much about beavers just shows you how you are affecting my subconscious as well as my conscious. However, if you had gone to well, let us say Smith, I’d think that small bearded men named Smith were following me.”

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

© 1935 Charles Addams With permission Tee and Charles Addams Foundation

“The funny thing about it, though, is that I finally did get an idea about beavers which I sold to The New Yorker,” he continued. “You see? You’re helping me to make good!” The Addams cartoon published in The New Yorker on May 25, 1935, showed beavers building a dam across a man-made water dam. “Hey, Griswold, look! Beavers!” an excited worker tells another.

During his breakthrough year of 1935, Addams finally found the matchless wash style which perfectly married his drawings to his subject. And his pen-line drawings, the popular style then, were soon replaced by his complex wash. Along with 21 cartoons and a spot drawing, he sold his first cover painting to The New Yorker, sold two originals, and published 4 cartoons in Collier’s. His success did not go to his head; it never would. And he never took a sale for granted. After submitting his cover painting – a dreamy, subdued picture of a white-haired astronomer wiping his spectacles as he stands before an enormous telescope– he told Jewell that he thought it would be used, but the magazine’s editor, Harold Ross,“wants to keep it on his desk to worry about it for a few days, and when he does that with a picture I always get pretty jittery.”

As Addams realized his dream of becoming a New Yorker artist, another dream slipped away. He asked Jewell to marry him. Evidently returning his affections, she had tea with his mother, who approved the match, but Jewell’s wealthy family did not. After hiring a lawyer to look into Charles Addams, they determined that he would never amount to anything.

Jewell transferred to the University of Wisconsin, where she met William Harley, an aspiring cartoonist. (Discouraged by The New Yorker and his father, Harley gave it up.) The Valentines again sent their lawyer to investigate. In spite of Harley’s scuffed shoes, they allowed the romance to proceed.

Invited to Jewell’s wedding in 1940, Charlie sent a crystal bud vase. Caught inside was a crystal teardrop.

Linda H. Davis is the author of three biographies: Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life, Badge of Courage: The Life of Stephen Crane; Onward and Upward: A Biography of Katharine S. White; and one e-book, Autism on the Farm: A Story of Triumph, Possibility, and a Place Called Bittersweet. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN.com, The New Yorker, and in other publications. The mother of two, Ms. Davis lives in Massachusetts with her husband, Chuck Yanikoski.

_________________________________________________________________

And speaking of Charles Addams and Linda Davis, AddamsFest 2021 is happening as we speak in Addams’s hometown of Westfield, New Jersey. Ms. Davis will be on hand, taking part in the Gomez Lecture Series. From the program:  ____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

Inked Out!

Yesterday was pub day for Joe Dator’s Inked: Cartoons, Confessions, Rejected Ideas and Secret Sketches From The New Yorker’s Joe Dator (Prospect Park Books).

[originally, yesterday’s Spill was to have been a two-parter, celebrating both the release of the Addams bio & Mr. Dator’s Inked, but technology nixed my plan]The Spill congratulates Mr. Dator, and encourages all who are in love with New Yorker cartoons & cartoonists to rush out and buy a copy at your favorite bookstore, or order a copy through Mr. Dator’s website.

I’ve said it before, and will gladly say it again: Mr. Dator is one of the best modern day New Yorker artists. He’s the real deal. Make space on your New Yorker library bookshelf, as there’ll no doubt be more Dator collections in our future.

For more on Mr. Dator, visit this brand new Case For Pencils post from Jane Mattimoe:

“Joe Dator Shares How He Made His Book”

LInda,

Thanks very much for publishing these letters online! As you mentioned in your book, getting ideas was always difficult, and these letters to Jewell perhaps show us a bit about how his cartoon ideas developed. What a find!

I would also urge everyone to buy your excellent biography of Charles Addams!

Pete Vack, Editor, VeloceToday.com