New Yorker Cartoon Department News

We learned yesterday, in an email to cartoonist contributors, that Rachel Perlman has joined the New Yorker staff as Assistant Cartoon Editor. She joins Colin Stokes, who is the Associate Cartoon Editor, and Emma Allen, the Cartoon Editor. Ms. Perlman had previously worked free-lance for the magazine.

We learned yesterday, in an email to cartoonist contributors, that Rachel Perlman has joined the New Yorker staff as Assistant Cartoon Editor. She joins Colin Stokes, who is the Associate Cartoon Editor, and Emma Allen, the Cartoon Editor. Ms. Perlman had previously worked free-lance for the magazine.

I believe that this is the first time, in The New Yorker‘s history, that the Cartoon Department has had a three person staff.

Here’s an Ink Spill piece from February 2018, about the changes over time:

The New Yorker’s Art Meeting: A Potted History

It’s tempting to believe that the structure of The New Yorker’s Art Department arrived fully formed in 1924 when Harold Ross, with his wife Jane Grant began pulling together his dream magazine. But of course, such was not the case.

What we know for certain is that once the first issue was out, Ross and several of his newly hired employees began meeting every Tuesday afternoon to discuss the incoming art submissions. The very first art meetings consisted of Ross, his Art Director, Rea Irvin, Ross’s secretary, Helen Mears, and Philip Wylie, the magazine’s first utility man. In no short order, Ralph Ingersoll, hired in June of ’25 joined the art meeting, and later still, Katharine White (then Katharine Angell), hired in August of ’25, began sitting in.

From James Thurber’s account in The Years With Ross we get a good idea of what took place at the meeting, which began right after lunch and ended at 6 pm:

In the center of a long table in the art meeting room a drawing board was set up to display the week’s submissions…Ross sat on the edge of a chair several feet away from the table, leaning forward, the fingers of his left hand spread upon his chest, his right hand holding a white knitting needle which he used for a pointer…Ross rarely laughed outright at anything. His face would light up, or his torso would undergo a spasm of amusement, but he was not at the art meeting for pleasure.

William Maxwell, who joined The New Yorker’s staff in 1936, told the Paris Review in its Fall 1982 issue:

Occasionally Mrs. White would say that the picture might be saved if it had a better caption, and it would be returned to the artist or sent to E. B. White, who was a whiz at this… Rea Irvin smoked a cigar and was interested only when a drawing by Gluyas Williams appeared on the stand.

And from Dale Kramer’s Ross and The New Yorker:

When a picture amused him Irvin’s eyes brightened, he chuckled, and often, because none of the others understood art techniques, gave a little lecture. There would be a discussion and a decision. If the decision was to buy, a price was settled on. When a picture failed by a narrow margin the artist was given a chance to make changes and resubmit it. Irvin suggested improvements that might be made, and Wylie passed them on to the artists.

In a letter to Thurber biographer, Harrison Kinney, Rogers Whitaker, a New Yorker contributor from 1926 – 1981, described the scene in the magazine’s offices once the art meeting ended:

The place was especially a mess after the weekly art meeting. The artists, who waited for the verdicts, scrambled for desk space where they could retouch their cartoons and spots according to what Wylie, or Katharine Angell, told them Ross wanted done.

Wylie was one of many artist “hand-holders” – the bridge between the editors and the artists. Some others who held this position were Thurber (briefly, in 1927), Wolcott Gibbs, Scudder Middleton, and William Maxwell. According to Maxwell, Katharine White’s hand-holding duties were eventually narrowed to just Hokinson and Peter Arno, the magazine’s prized artists.

Lee Lorenz wrote in his Art of The New Yorker that, in the earliest years, the look of the magazine:

had been accomplished without either an art editor in the usual sense or the support of anything one could reasonably call an art department.

That changed in 1939 when former gagman, James Geraghty was hired. As with so much distant New Yorker history, there’s some fuzziness concerning exactly what Geraghty was hired to do. Geraghty, in his unpublished memoir, wrote that he took the job “without any inkling” of what was required of him. There’ve been suggestions in numerous accounts of New Yorker history, that Geraghty was hired as yet another in the lengthening line of artist hand-holders, in this case, succeeding William Maxwell, who was increasingly pre-occupied with his own writing as well as his editorial duties under Katharine White.

Geraghty, in his memoir, recalled his first art meeting and the awkwardness of sitting next to Rea Irvin: two men seemingly sharing one (as yet unofficial, unnamed) position: Art Editor. While E.B. White and others continued to “tinker” with captions, Geraghty began spending one day a week working exclusively on captions. He also adopted the idea that he was the Artists’ “representative” at meetings, following Ross’s assurance that Geraghty was being paid “to keep the damned artists happy.”

With these new components, the art meeting committee model stayed in place until the death of Ross in December of 1951. When William Shawn officially succeeded Ross in January of 1952, he pared the meeting to two participants: Shawn, and Geraghty.

With Geraghty’s retirement in 1973, and Lee Lorenz’s appointment as Art Editor, the art meetings continued with Lorenz and Shawn. Shawn’s successor, Robert Gottlieb and then Tina Brown, subdivided the Art Department, creating a Cartoon Editor, an Art Editor (for covers) and an Illustration Editor. Lorenz, who was in the midst of these modern day changes, lays them out in detail in his Art of The New Yorker.

Today, [but not currently during the work-at-home Pandemic period] the Shawn model Art Meeting continues, with the current Editor, David Remnick, and the current Cartoon Editor, Emma Allen (and with a third editor occasionally joining the meeting) sitting down one day a week to look through the pile of drawings Ms. Allen has distilled from the mountain submitted to the magazine. The cartoonists no longer wait outside the Art Meeting’s door for the verdict on their work, but I assure you: wherever they are on Thursday or Friday afternoon: they’re waiting.

_________________________________________________________________

Chast Lecture At Amherst: “Can’t We Talk About Something More Jewish?”

From The University of Massachusetts At Amherst website, “Cartoonist And Best-Selling Author Roz Chast To Deliver 2022 Robert And Pamela Jacobs Lecture”

From The University of Massachusetts At Amherst website, “Cartoonist And Best-Selling Author Roz Chast To Deliver 2022 Robert And Pamela Jacobs Lecture”

— The title of the lecture is, of course, a play on Ms. Chast’s 2016 best-seller, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

Ms. Chast began contributing to The New Yorker in 1978. Visit her website here.

–Photo by Bill Franzen

___________________________________________________________________

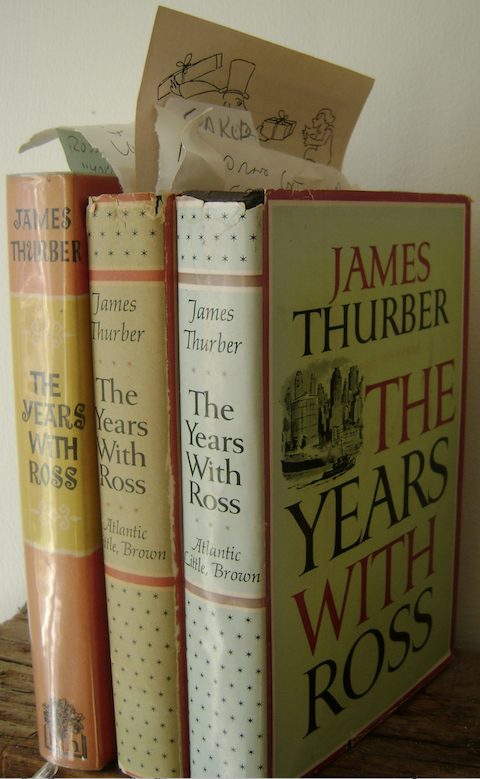

Bookstore Find Of The Week: The Years With Ross

Bookstore Find Of The Week: The Years With Ross

Alerted by my younger daughter to a new (new to me) used bookstore in our area, she, her significant other, and I, paid a visit yesterday.

After a good amount of time perusing the store’s vast inventory, we were about to purchase our found treasures when one of my bookstore haunting pals said to the other, “Did you you tell him about the Thurber book?”

At that the three of us walked at a fast clip over to the biography section, where we zeroed in the book. As it left the shelf I immediately recognized it as Thurber’s The Years With Ross, and also recognized that the cover was still shiny (the book was first published in 1959).

“Are you going to buy it?” I was asked as I flipped through the pages. “Of course!” was my reply, followed by laughter, and the question I knew was coming next: “How many copies of this do you already have? I didn’t have a ready reply.

I do know that there are now three copies at hand near the table where I work. They’re shown here: on the left is the UK copy, published by Hamish Hamilton, then my well-thumbed everyday go-to copy, and the latest addition.

Without checking the other copies in the Spill library I’m almost certain this newly acquired copy is in the best condition of the lot (excepting the UK copy). In the Spill library are various paperback editions, and (a guess) at least two or three other hardcover copies.

The book is, without a doubt, one of my favorite Thurber books. But even if it wasn’t, I would’ve bought it yesterday. It cost one dollar.