The Fourth New Yorker Album of drawings, published in 1931 by Doubleday Doran, was the fourth Album to appear in four years (the first Album was published in 1928). Four in four years! The cover, originally a New Yorker cover (for the issue of January 4, 1930 — see directly below) is the handiwork of the one-and-only Rea Irvin, the fellow responsible for Eustace Tilley, as well as the fellow responsible for adapting the typeface now referred to as the Irvin Typeface…and last but not least of all: the fellow who, in his role as the New Yorker‘s art supervisor, “rubbed most of the uncouthness and corn-love out of [Harold] Ross’s mind in the all afternoon Tuesday art conferences…Irvin educated Ross; all afternoon, weekly, for nearly two years.” (according to Philip Wylie, the magazine’s first “bona fide applicant”).

The Foreword, by Robert Benchley is, of course, priceless. It includes these memorable moments:

“As a constant though erratic contributor of text matter to the New Yorker and one or two other publications, I feel that I am in a position to state the (to me) distressing fact that the average magazine reader looks only at the drawings.”

“There is something consecutive about the drawings in the New Yorker, like salted almonds. You finish with one and you must go right on to the next just as quickly as possible.”

Mr. Benchley concludes with: “All right — go ahead and look at your old pictures!”

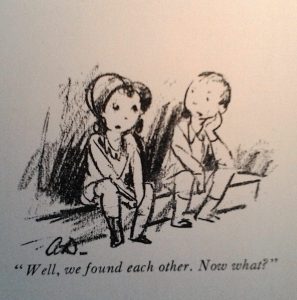

The old pictures — just a year old at most — are fantastic. The Album leads off with a full page Peter Arno (by now the New Yorker‘s star cartoonist) and ends in what I find to be one of the sweetest final pages in all of the magazine’s Albums. It’s not a grand exercise in drawing, or a famous drawing or a drawing with a caption that captures the times (it being 1931, there certainly could’ve been a statement made about the Great Depression. But, ah! Mr. Irvin’s cover of the overblown rich gent accomplished that). The final drawing, by Alan Dunn (shown below) is just 2 1/4″ x 3″ (centered on an 8 1/2″x 11″ page):

Placed as the Album’s last drawing I can’t help but think its meant to mean something beyond two little kids sitting on a curb who have just become friends, or as Neil Young sang, “There’s more to the picture than meets the eye.” Perhaps (perhaps!) it was representative of a confident young magazine slyly addressing a loyal readership.

In between Mr. Arno’s drawing on the first page and Mr. Dunn’s drawing on the last page are an abundance of spectacular drawings. And by that I’m not referring to just the drawing — I mean the whole cartoon: caption + drawing (as well as those gems that work perfectly without a caption). There are of course, some drawings with meanings lost to time, a clunker here and there, and a number that are not politically correct. But no matter — they are instructive as an unvarnished graphic record of a time, and as a study in the art of the cartoonists themselves: the early Thurber drawings that inspired Dorothy Parker to refer to them as “unbaked cookies”; Arno’s drawings at the tail end of his Daumier-inspired period, just before he swung into Rouault’s camp; masterful drawings by, among others, Garrett Price, Ralph Barton, Helen Hokinson, Wallace Morgan, William Steig, Carl Rose, Gardner Rea, and Gluyas Williams (of course!). Below are just a few examples of the art within the Fourth:

The back of the Album is a first: an advertisement for another New Yorker publication: The New Yorker Scrapbook, comprised of “text matter” to use Mr. Benchley’s words. Despite the ad exhibiting glimpses of art, there is not a single drawing in the Scrapbook, not even a spot.

Perhaps this is as good a time as any in this Sunday series to drag out an essay I wrote back in 2008 (slightly updated this morning), “The Art Meeting: A Potted History.” Many of the albums discussed here, thus far, and those to come, exhibit work chosen under the magazine’s earliest editorial “process” during the magazine’s first 25 years. The format changed in 1952, with William Shawn’s installation as the magazine’s editor. That model (or at least a version of that model) is still in place today. Two very different ways of choosing the magazine’s art, both worth examining:

It’s tempting to believe that the structure of The New Yorker’s Art Department arrived fully formed in 1924 when Harold Ross, with his wife Jane Grant began pulling together his dream magazine. But of course, such was not the case.

What we know for certain is that once the first issue was out, Ross and several of his newly hired employees began meeting every Tuesday afternoon to discuss the incoming art submissions. The very first art meetings consisted of Ross, his Art Director, Rea Irvin, Ross’s secretary, Helen Mears, and Philip Wylie, the magazine’s first utility man. In no short order, Ralph Ingersoll, hired in June of ’25 joined the art meeting, and later still, Katharine White (then Katharine Angell), hired in August of ’25, began sitting in.

From James Thurber’s account in The Years With Ross we get a good idea of what took place at the meeting, which began right after lunch and ended at 6 pm:

In the center of a long table in the art meeting room a drawing board was set up to display the week’s submissions…Ross sat on the edge of a chair several feet away from the table, leaning forward, the fingers of his left hand spread upon his chest, his right hand holding a white knitting needle which he used for a pointer…Ross rarely laughed outright at anything. His face would light up, or his torso would undergo a spasm of amusement, but he was not at the art meeting for pleasure.

William Maxwell, who joined The New Yorker’s staff in 1936, told the Paris Review in its Fall 1982 issue:

Occasionally Mrs. White would say that the picture might be saved if it had a better caption, and it would be returned to the artist or sent to E. B. White, who was a whiz at this… Rea Irvin smoked a cigar and was interested only when a drawing by Gluyas Williams appeared on the stand.

And from Dale Kramer’s Ross and The New Yorker:

When a picture amused him Irvin’s eyes brightened, he chuckled, and often, because none of the others understood art techniques, gave a little lecture. There would be a discussion and a decision. If the decision was to buy, a price was settled on. When a picture failed by a narrow margin the artist was given a chance to make changes and resubmit it. Irvin suggested improvements that might be made, and Wylie passed them on to the artists.

In a letter to Thurber biographer, Harrison Kinney, Rogers Whitaker, a New Yorker contributor from 1926 – 1981, described the scene in the magazine’s offices once the art meeting ended:

The place was especially a mess after the weekly art meeting. The artists, who waited for the verdicts, scrambled for desk space where they could retouch their cartoons and spots according to what Wylie, or Katharine Angell, told them Ross wanted done.

Wylie was one of many artist “hand-holders” – the bridge between the editors and the artists. Some others who held this position were Thurber (briefly, in 1927), Wolcott Gibbs, Scudder Middleton, and William Maxwell. According to Maxwell, Katharine White’s hand-holding duties were eventually narrowed to just Hokinson and Peter Arno, the magazine’s prized artists.

Lee Lorenz wrote in his Art of The New Yorker that, in the earliest years, the look of the magazine:

had been accomplished without either an art editor in the usual sense or the support of anything one could reasonably call an art department.

That changed in 1939 when former gagman, James Geraghty was hired. As with so much distant New Yorker history, there’s some fuzziness concerning exactly what Geraghty was hired to do. Geraghty, in his unpublished memoir, wrote that he took the job “without any inkling” of what was required of him. There’ve been suggestions in numerous accounts of New Yorker history, that Geraghty was hired as yet another in the lengthening line of artist hand-holders, in this case, succeeding William Maxwell, who was increasingly pre-occupied with his own writing as well as his editorial duties under Katharine White.

Geraghty, in his memoir, recalled his first art meeting and the awkwardness of sitting next to Rea Irvin: two men seemingly sharing one (as yet unofficial, unnamed) position: Art Editor. While E.B. White and others continued to “tinker” with captions, Geraghty began spending one day a week working exclusively on captions. He also adopted the idea that he was the Artists’ “representative” at meetings, following Ross’s assurance that Geraghty was being paid “to keep the damned artists happy.”

With these new components, the art meeting committee model stayed in place until the death of Ross in December of 1951. When William Shawn officially succeeded Ross in January of 1952, he pared the meeting to two participants: Shawn, and Geraghty.

With Geraghty’s retirement in 1973, and Lee Lorenz’s appointment as Art Editor, the art meetings continued with Lorenz and Shawn. Shawn’s successor, Robert Gottlieb and then Tina Brown, subdivided the Art Department, creating a Cartoon Editor, an Art Editor (for covers) and an Illustration Editor. Lorenz, who was in the midst of these modern day changes, lays them out in detail in his Art of The New Yorker.

Today, the Shawn model Art Meeting continues, with the current editor, David Remnick looking through the pile of drawings the current cartoon editor, Emma Allen, has distilled from the mountain submitted to the magazine. The cartoonists no longer wait outside the Art Meeting’s door for the verdict on their work, but I assure you: wherever they are on a Friday afternoon (when the artists are notified if they’ve sold a drawing): they’re waiting.

— originally p