Ink Spill occasionally takes a look at New Yorker contributors who weren’t cartoonists but whose work at the magazine was so intertwined with cartoons and/or cartoonists that it would be just plain silly not to look at them. Peter De Vries, a New Yorker staffer from 1944 through 1986, fits the bill perfectly.

Ink Spill occasionally takes a look at New Yorker contributors who weren’t cartoonists but whose work at the magazine was so intertwined with cartoons and/or cartoonists that it would be just plain silly not to look at them. Peter De Vries, a New Yorker staffer from 1944 through 1986, fits the bill perfectly.

De Vries, who died in 1993, moved from his hometown, Chicago, to the east coast and The New Yorker via James Thurber, who highly recommended De Vries to the magazine’s founder and editor, Harold Ross.

Hired to work part-time in the magazine’s poetry department, De Vries wrote for Notes and Comment, as well as contributing fiction. After asking the magazine’s Art Editor, James Geraghty if there was anything he could do in the Art Department, De Vries was taken in as a “cartoon doctor” in 1947, fixing captions, helping to develop ideas, and sometimes coming up with his own. Unless my computations are wrong, no other New Yorker editor had as long an association with the magazine’s cartoons as De Vries: thirty-nine years.

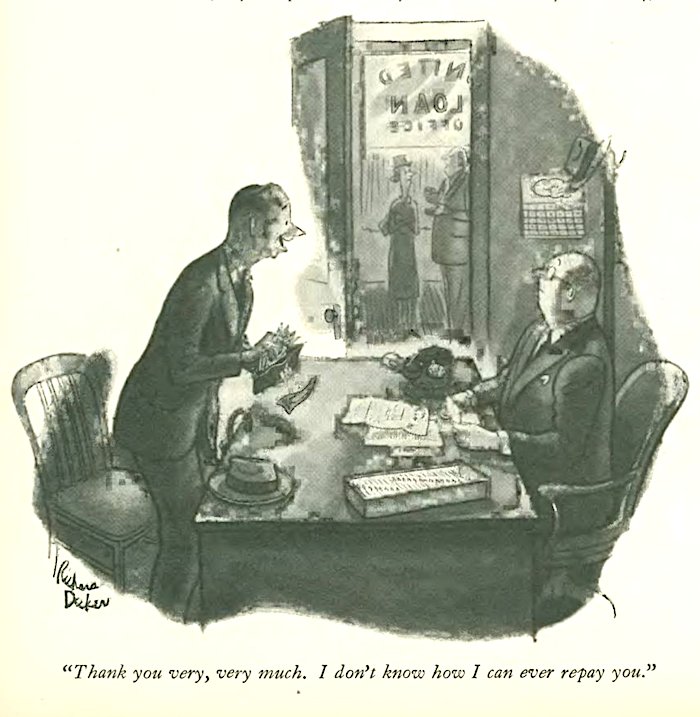

In various interviews over the years, he seemed reticent to discuss his duties concerning cartoons. Ben Yagoda, who interviewed him for The New York Times in 1983, reported that De Vries couldn’t recall any original cartoon ideas he came up with, except one: a drawing by Richard Decker that appeared in July 21, 1945 (shown here). Yagoda surmised that “DeVries hesitancy to discuss his work in the Art Department may spring from a desire to uphold the myth that cartoonists’ works are never altered.” That myth is worth exploring at another time, but perhaps it was less an allegiance to the myth and more of a De Vries personality trait. Former New Yorker Art/Cartoon Editor, Lee Lorenz, who was recently interviewed for this piece, described De Vries as “very quiet – sort of shy.” In a 1956 interview with The New York Times, De Vries described himself as “‘utility man in the Art Department,’ while others around the place describe him as a force in the Bull Pen.”

In various interviews over the years, he seemed reticent to discuss his duties concerning cartoons. Ben Yagoda, who interviewed him for The New York Times in 1983, reported that De Vries couldn’t recall any original cartoon ideas he came up with, except one: a drawing by Richard Decker that appeared in July 21, 1945 (shown here). Yagoda surmised that “DeVries hesitancy to discuss his work in the Art Department may spring from a desire to uphold the myth that cartoonists’ works are never altered.” That myth is worth exploring at another time, but perhaps it was less an allegiance to the myth and more of a De Vries personality trait. Former New Yorker Art/Cartoon Editor, Lee Lorenz, who was recently interviewed for this piece, described De Vries as “very quiet – sort of shy.” In a 1956 interview with The New York Times, De Vries described himself as “‘utility man in the Art Department,’ while others around the place describe him as a force in the Bull Pen.”

Frank Modell, now age 95, and the New Yorker’s eldest cartoonist, was good friends with De Vries, interacting with him weekly at the magazine’s office during the time Modell was Geraghty’s assistant in the 1940s. Modell told me recently, “De Vries was an amazingly good humored guy.” Distilling De Vries’ work with cartoons, Modell said, “he made [captions] a little more clear.”

When Lorenz succeeded James Geraghty as Art Editor in 1973, a sea-change was underway at the Art Department. Idea men (there were no idea women) who had supplied some of the great New Yorker cartoonists with a steady stream of excellent work, were facing a new wave of cartoonists who were in the mold of Thurber – an artist who wrote all of his own ideas — and not George Price, a cartoonist who relied completely on ideamen.

Lorenz, reflecting on that time, and the waning of idea men:

“Of course there was a long tradition there of people who just did the ideas and the artists who just did the drawings, but we’d gotten past that by that point. Artists did their own stuff. If he [De Vries] came up with a good one I’d certainly take it back to the artist, and they’d have the final word –- it was their caption.

I’ve thought about it a lot — there’s a big difference between writing humor and captioning a cartoon. There’s a special skill to writing captions. He was a funny writer, but when he tried to change a caption, it got longer, it got more convoluted.”

Asked to describe his working relationship with De Vries, Lorenz said:

“We were friendly, but I hardly ever saw him. He kept pretty much to himself there. The stuff [sheets of paper bearing copies of approved cartoons for that week] would be shipped out to his office at some point during the week and he’d go through it. He didn’t come to the art department. All this stuff would be passed around in a box – a regular wooden box. It would go down to his office and he would go through it and make notes and eventually it would come back to me. But I don’t remember we discussed much of this face to face. We weren’t avoiding each other — that was just the kind of relationship we had.

De Vries, a prolific novelist, did not shy away from using his New Yorker Art Department experience in his popular 1954 book, The Tunnel of Love. It’s the story, in a nutshell, of a fellow named Dick, who is Cartoon Editor of The Townsman, a New Yorker-like magazine, and another fellow, Augie, who’s a third-rate cartoonist and first rate idea man.

De Vries, a prolific novelist, did not shy away from using his New Yorker Art Department experience in his popular 1954 book, The Tunnel of Love. It’s the story, in a nutshell, of a fellow named Dick, who is Cartoon Editor of The Townsman, a New Yorker-like magazine, and another fellow, Augie, who’s a third-rate cartoonist and first rate idea man.

If cartoon aficionados have one reason to hold De Vries in high regard it would certainly be for the part he played in developing one of Charles Addams most enduring cartoons (and a captionless one at that). In the fall of 1946, James Geraghty, in need of a Christmas cover, invited De Vries over to his Connecticut home to sit out on the front lawn and brainstorm. The result was the classic Addams cartoon that appeared in the December 21, 1946 New Yorker: three members of the so-called Addams Family, four stories up, about to pour boiling oil on the carolers below. Although Geraghty and De Vries conceived of it as a cover, Harold Ross nixed the idea and ran it inside as a full page cartoon.

Below: De Vries first book, published in 1940, cover by Charles Addams

Special thanks to Lee Lorenz and Frank Modell for their assistance with this piece. Lee Lorenz interviewed April 9, 2013; Frank Modell interviewed April 11, 2013