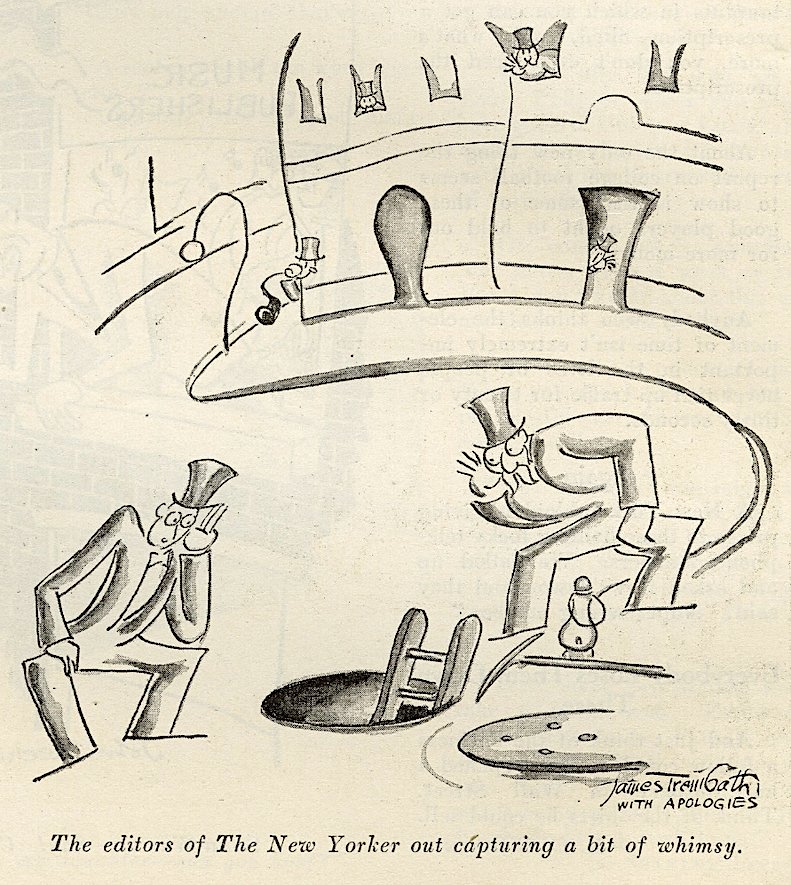

A few months back my New Yorker colleague, Paul Karasik, sent in a page from the November 18 1929 issue of Judge that included this drawing by James Trembath (I’m sorry to say I can’t find anything on Mr. Trembath):

The artist was gently poking at The New Yorker as well as one of its artists, Otto Soglow, who by the Fall of 1929 had contributed 27 of an eventual total of 36 manhole themed drawings to the magazine. Most of those 36 were part of a series, using the exact same drawing, and substituting different captions.

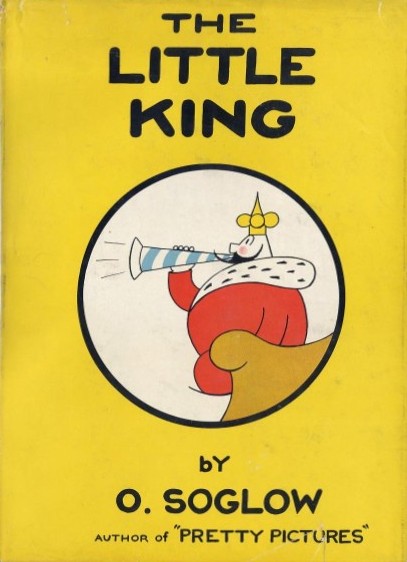

When most of us think of Soglow we probably think of his most famous creation, The Little King — I doubt many think of Soglow’s manhole drawings. Yet they were quite a presence in The New Yorker for a while (granted it was a long long time ago). I’ve been aware of them over the years, running into them as I thumbed through ancient issues of the magazine. Trembath’s Judge drawing caused me to dig into Soglow’s manhole drawings just a little more.

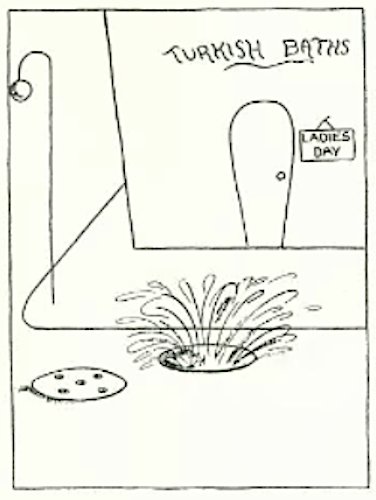

The first Soglow manhole drawing appeared in The New Yorker in the issue of November 5, 1927.* It was the first of two prequels (of sorts) to the classic series that followed. Unlike the long-running one-panel series this first manhole drawing is a three-parter:

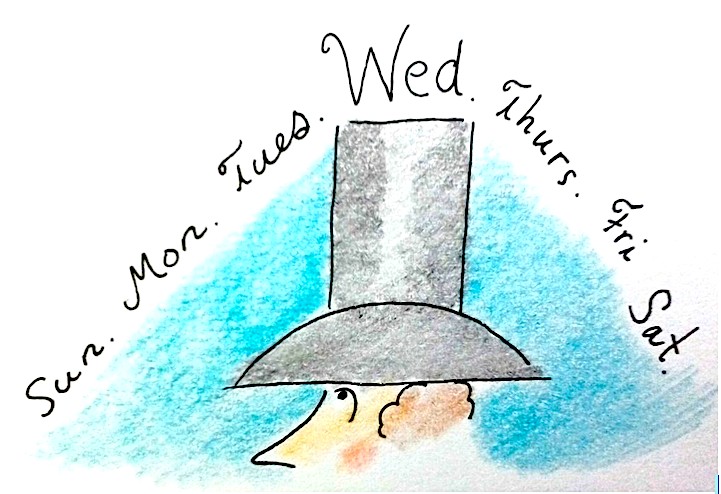

It was followed by this interesting drawing (layout-wise) from the issue of May 5, 1928. The drawing cuts through the text; the text has nothing to do with the drawing:

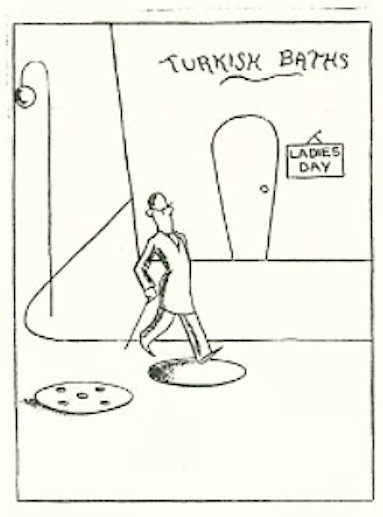

The series that the artist James Trembath was referring to begins in the issue of December 15, 1928. This is the blueprint for the next dozen years of the series. As far as I can tell, the drawings are identical. The only thing that changes from drawing-to-drawing is the caption.

Soglow almost always uses the name”Bill” when he needs a name in one of the manhole drawings. There are a few exceptions: an example from the issue of January 5, 1929:

Here’s the last of the series, from the issue of October 17, 1931:

When the manhole theme returns (in the issue of September 20, 1941), it’s no longer part of the earlier series. The style and the old blueprint is history. There are only three Soglow manhole drawings left after this:

This is the last of them (May 22, 1948):

Jared Gardner, in his Introduction to Cartoon Monarch: Otto Soglow and The Little King, reads this into the manhole series:

“While at first it might seem that the joke is at the expense of sewer workers who imagine that they have the right to opinions on aesthetics or philosophy, soon the cumulative effect of the series makes clear that the joke is instead directed at the highbrow reader who cannot for a moment imagine the workers toiling below his feet as human beings possessed of a love of truth and beauty.”

If that’s true, or if Soglow had simply found a terrific vehicle to revisit, we’ll never know. Maybe, as is so often the case with cartoonists, the truth contains a little of both.

It doesn’t seem quite fair (given all the effort Soglow put into these drawings), but when I think of New Yorker manhole drawing cartoons I don’t immediately think of Soglow’s work — I think of this one by Charles Addams.

— My thanks to Paul Karasik for sending the Trembath cartoon, and thus sparking my dive into the Soglow pieces.

*Jared Gardner, in his introduction to Cartoon Monarch says that Soglow’s manhole theme began in The New Yorker in 1926, but I didn’t spot a manhole in any of the four Soglow drawings that appeared that year. _________________________________________________________________________

Otto Soglow’s A-Z Entry

Otto Soglow Born, Yorkville, NY, December 23, 1900. Died in NYC, April 1975. New Yorker work: 1925 -1974.Key collections: Pretty Pictures ( Farrar & Rinehart, 1931) and for fans of Soglow’s Little King; The Little King (Farrar & Rinehart, 1933) and The Little King (John Martin’s House, Inc., 1945). The latter Little King is an illustrated storybook. Cartoon Monarch / Otto Soglow & The Little King (IDW, 2012) is an excellent compendium.

So now I’m looking up James Trembath. Apparently he did many covers for Judge. 🙂

https://www.comics.org/creator/26649/

If you find any biographical information on Trembath, please let me know, Martha. I’d like to link to it in the Soglow post.