We’re just a couple of days from the publication of The New Yorker‘s 100th anniversary issue. I thought this as good a time as any to toast Harold Ross, the fellow who invented the magazine, along with his wife, Jane Grant. Together they figured out the look, the financing, and the content of (in Ms. Grant’s words) the “introductory number.” And together they worked on the slender issues that followed the magazine’s debut in 1925.

We’re just a couple of days from the publication of The New Yorker‘s 100th anniversary issue. I thought this as good a time as any to toast Harold Ross, the fellow who invented the magazine, along with his wife, Jane Grant. Together they figured out the look, the financing, and the content of (in Ms. Grant’s words) the “introductory number.” And together they worked on the slender issues that followed the magazine’s debut in 1925.

Before that first issue hit the newsstand, before it had a name, it existed as Ross’s dream in the form of a dummy. Ross, according to George Kaufman, “carried a dummy of the magazine for two years, everywhere, and I’m afraid he was rather a bore with it.”

I’m not sure I’ll ever understand Ross. But does that even matter? No, it doesn’t. It’s plenty enough to understand that he was driven to publish a magazine unlike any other, one that would, for the most part, run from convention.

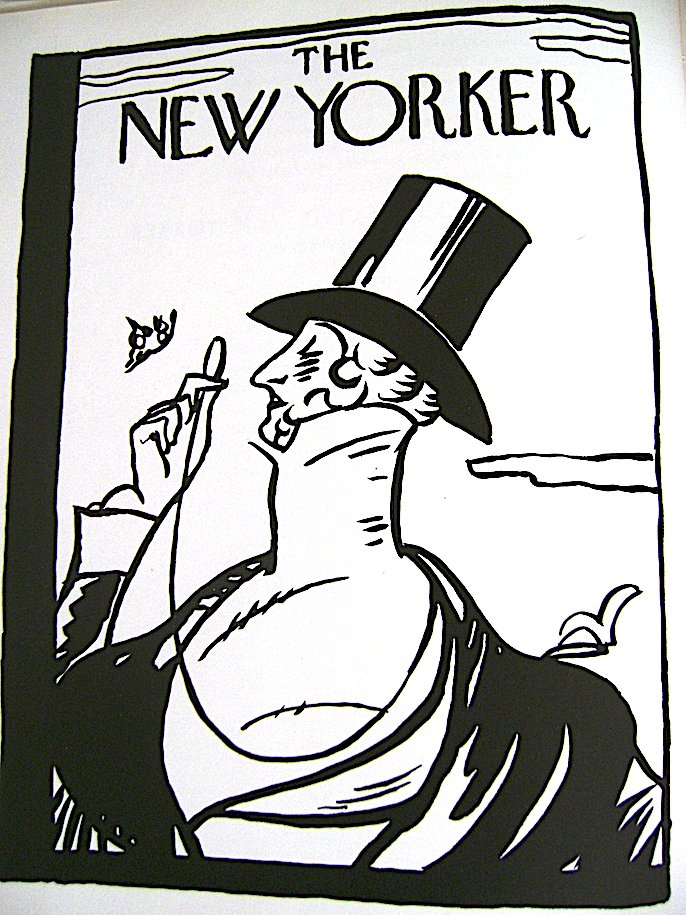

The other day I mentioned how wonderful it was that the debut issue’s cover carried no hint of what was inside. The cover featured a man from the past — not some artist’s or editor’s idea of the present or future. Not something that screamed from the newsstand. A puzzlement! Like so much else of Ross’s magazine, that first issue, from cover-to-cover, promised the unconventional.

The other day I mentioned how wonderful it was that the debut issue’s cover carried no hint of what was inside. The cover featured a man from the past — not some artist’s or editor’s idea of the present or future. Not something that screamed from the newsstand. A puzzlement! Like so much else of Ross’s magazine, that first issue, from cover-to-cover, promised the unconventional.

left: Rea Irvin’s man from the past

Some people say the debut issue was a graphic mess, that it was confusing, that it was derivative, that it didn’t seem to know what it was about. All true in a way — the magazine was most definitely a testing ground. It was Ross’s testing ground. But from the start he embraced curiosity, and insisted on accuracy and clarity (we’ve heard how much he adored Fowler’s “Modern English Usage”).

If you’ve been following The New Yorker‘s story you’ve likely encountered the two schools of thought about Ross. Let’s call one the “Is Moby Dick the man or the whale?” school. In that school, Ross is the enigmatic gap-toothed tramp reporter from out west who somehow stumbled into creating The New Yorker. Then there’s the E.B. White and Katharine White school. The Whites considered writing their own history of the magazine to counter the Moby Dick school. It’s a pity they never did. In E.B. White’s obit of Ross in the magazine’s issue of December 15, 1951 he wrote in part:

What I know about the magazine Ross created is this: as it came along through the years, it kept the best stuff — that “natural drive in the right direction” — and found even more good stuff and held onto it. John Updike called the magazine (I’m paraphrasing here) a sheltering place. For certain writers, artists, and editors, nothing could be truer. Ross’s “respect for the work and ideas and opinions of others” allowed them, encouraged them to thrive.

What I know about the magazine Ross created is this: as it came along through the years, it kept the best stuff — that “natural drive in the right direction” — and found even more good stuff and held onto it. John Updike called the magazine (I’m paraphrasing here) a sheltering place. For certain writers, artists, and editors, nothing could be truer. Ross’s “respect for the work and ideas and opinions of others” allowed them, encouraged them to thrive.

In 1924, Ross and Jane Grant, on their way to producing “the introductory number,” covered their living room floor with the popular magazines of the day, absorbing what they liked, eschewing what they didn’t. What they didn’t like — and why they didn’t like it! — went a long way to forming the magazine that has now been around a hundred years.

Above: an in-house parody issue. Ross peers at Alexander Woollcott