Ed Koren, who passed away this past April, would’ve turned 88 today. The Spill celebrates Ed’s birthday with a special contribution from his long-time friend, the author Howard Norman (shown below, center left, with Ed in 1990).

I contacted Mr. Norman after hearing him speak at Ed’s memorial in September. At the memorial, Mr. Norman spoke of a haiku series he and Ed were working on (“No Conversation Long Enough: Ed Koren’s Haiku Dialogues” is in progress); specifically mentioned was the turtle haiku discussed below. In this piece, Mr. Norman talks more about the haiku series, and his working relationship with Ed.

My thanks to Howard Norman for this wonderful insight into New Yorker cartoonist extraordinaire, Ed Koren.

Edward Koren: Haiku Dialogues

The manuscript of “Edward Koren: Haiku Dialogues,” comes to 178 typewritten pages. My process was uncomplicated: I wove together notes, some nearly stenographic, others a few hours after the fact, with transcriptions of tape recordings of what Ed referred to as our “haiku dialogues,” which largely were about his drawings made to accompany various haiku I provided from 2013 to 2023. With a few exceptions, our haiku dialogues took place during a monthly dinner at Kismet restaurant or Three Penny Taproom in Montpelier, but also there were a good number of decidedly briefer meetings at his and Curtis’ house in Brookfield, Vermont during the the varied confinements of Ed’s final year. He kept two thick folders: HAIKU and ORIGINAL SMALL HAIKUS, each replete with typed or handwritten haiku, sketches, marginalia, queries. There are fifty-six haiku drawings.

Simply put, after Ed had been diagnosed with lung cancer, our haiku dialogues ever more frequently included the nature of friendship, and his eclectic reading, what Ed called “my education in the mortal realm.” (The question of what criterion does one use to decide whether or not one has had a “full life” was, in his final eighteen months, very much on his mind) — : this is to say, there were all sorts of somber and comical takes on life, as Ed had been mulling things over. The philosopher we read together, Schopenhauer (I have a drawing of a wild-haired Koren creature meant to be Schopenhauer himself; wearing a THE WORLD AS WILL AND REPRESENTATION t-shirt, he’s pleading with the maitre d, “I’d like to be seated near a raucous table where I won’t be allowed serious thought, PLEASE.”) also provided grist for the mill. Particularly compelling to Ed was Schopenhauer’s assertion that mostly it’s loss that teaches us the worth of things. Ed approached this from many angles. It seemed to show up in our talks quite often.

Our final haiku dialogue (with whiskey) took place on April 12, 2023, a couple of days before he died. On that occasion, we again spoke about a favorite haiku by Sato: “Old turtle knows/what love is/won’t tell me.” I’d brought his drawing along for us to look at. “I like this drawing a lot,” he said. “It feels completed. I don’t feel that about a lot of my haiku drawings. I needed more time with those. That’s why I’m taking my pencils into the Bardo.”

Truth be told, Ed was at best skeptical about any sort of afterlife. (I have his drawing, a kind of self-portrait, in which Ed is standing in his studio; a banner reads: BARDO SALE: pencils, paper, conversation with the cartoonist, all half-price. LIMITED TIME ONLY”). Suffice it to say that he took his “education in the mortal realm” from all sorts of spiritual disquisitions, poetry, aphorism, texts. He loved Talmudic paradoxes and conundrums as found, for instance, in Martin Buber’s Hassidic Tales, and came up with this joke: “If granted an audience, I’d tell God that I’m an atheist.” As for his meditations on death, he said, “I don’t expect answers. I only need to try for some original way of thinking about my demise. I don’t mind borrowing, but I don’t want to be reliant. I prefer to be part of the curmudgeon school of thought. It’s more me.” Anyway, haiku became yet another source of delight, curiosity, introspection, and yes, his personal brand of scholarship.

Generally the way it worked was, I’d send Ed, by post or email, one, several or even a bunch of haiku; these came from all manner of bibliography. There was, for example, “The Essential Haiku,” edited and translated by Robert Hass. There was “On Haiku” by Hiroaki Sato. There was “Selected Haiku of Yosa Buson,” translated by W.S. Merwin and Takako Lento. There was “Far Beyond the Field: Haiku by Japanese Women,” translated by Makota Ueda. But there were also examples of “western” haiku, by Jack Kerouac, Anselm Hollo, Caroline Kizer, Gerald Vizenor, Richard Wright and many others. If there was one collection he spoke of most often, it was “The Kobe Hotel” by Saito Sanki; if there was one haiku writer whose life he particularly wanted to inquire and talk about, it was Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902), who was so often bedridden with tuberculosis. (“I’ve become bedridden like Shika” he said in March, 2022). In the end, our shared bibliography came to one hundred forty-one sources.

“These haiku have enspirited my craft — my drawing,” he said. That was his phrase, “enspirited my craft.” You will see in this first entry — and many subsequent entries — how he spoke of “the relationship of mood, content and line,” as he put it. It took him three days to get to the expression of the turtle just right.

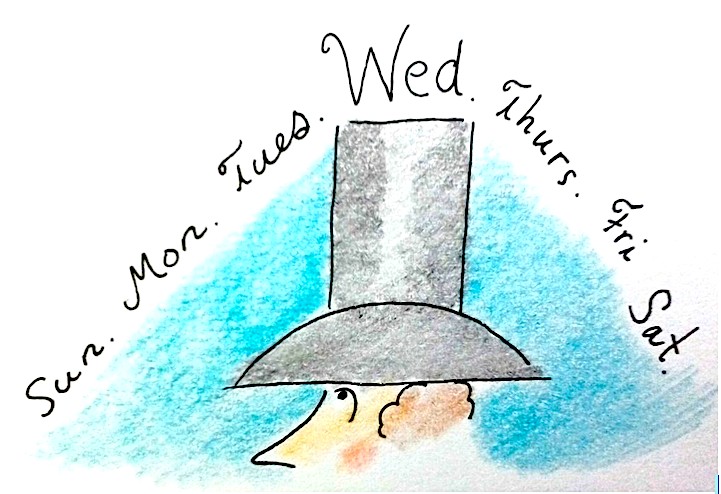

OLD TURTLE KNOWS/WHAT LOVE IS/WON’T TELL ME

August 11, 2019

“All day I’ve been in high dungeon,” he said. “Too many dreaded errands. Not enough time in the studio. Or on my bike.” We met at Three Penny Taproom at 7:00 and right away Ed took a haiku drawing out of his satchel. “This is one of my favorites,” he said. Sipping his usual dry martini, he became what he often referred to as his “docent self,” gave me a brief lecture on what I should pay attention to in this particular drawing. “Mood, content, line — it’s all here. I had to give the turtle a very bemused expression. The fellow on top of the turtle, he’s the narrator, or the author of the haiku — I guess that’d be Sato. What I especially love about this haiku is the pathos. Was it Freud — not sure — who spoke of the power of withholding, so that’s what the turtle is doing, withholding precious information: what is love? The “won’t” is the thing. Why won’t he? Maybe love can’t ever be defined, but the poet feels the turtle knows what it is, and that’s what sort of sets up the comical tension. The turtle — or tortoise — it might live a hundred years, the poor fellow could ride around on its back forever, you know, “What is love? What is love? What is love?” One slow step at a time over hill and dale: “What is love? Come on, tell me, what is love?” But it’s a haiku, it’s not a long narrative, it’s a moment in time. That’s what I think is so important. The “won’t” is emphatic — and maybe permanent. I thought a lot about the bemused expression on the face of the turtle. How dare he look bemused in the face of such a big question! I think that’s both funny and sad. It’s all contained in the moment. It’s also the silence of it all I was interested in. The no-dialogue part. The only thing this fellow has at his disposal is not knowledge of love, but the ability to write the haiku. That’s all he gets, really. To state the cold hard fact of not getting vital information — within the timeless poem. and the lines: the turtle — its composition, its lines — is quite organized, right? But the fellow himself: it’s like his feathers are ruffled, like he’s gone a bit mad by what he can’t ever know. Okay, enough of my docent self — I want to finish my martini. Then let’s order.”

During dinner we talked about a painter friend of his (“her last exhibit was reliable with all the signature elements, but tired”) we talked about my novel I’d given Ed in manuscript — he had useful critical comments, but only a few; we talked about our children; we talked about a recent “incident” on the floating bridge in Brookfield; we talked about the five preliminary sketches for cartoons he’d sent in that week. We talked longest about Biography, the play by Max Frish. I’d sent him a dvd of the performance (Frish wrote in German but the performance was in French translation) that took place in Paris — Ed is fluent and didn’t need subtitles, which was good because there weren’t any. In the play, a middle-aged behavioural researcher, Kurmann, is given the chance to start over with his life at any given point and “correct” any previous choices he made — from his failed marriage, his lack of political conviction and his successful academic career, to his poor attention to health, and the color of his living room furniture. Yet despite his intention to apply whatever wisdom he acquired, Kurmann finds himself inexorably trapped by the same decisions. Ultimately proving fatal, Kurmann’s life “game” in interrogates how much of our own path is shaped by other, seemingly random factors and how much is in fact predetermined by our own limited, conditional selves. I suppose that — and Frish is a maestro at such tropes — one of the play’s central ideas is that our lives are nothing but a self-conscious play with imaginary identities. And truly it is comic and tragic in equal measure.

“I loved the play,” he said.

“Yes, you know, the old salt: if you had a chance to live your life over again, would you?” I said.

“Not me,” Ed said. “but I’d like to keep trying to figure out exactly what life I’d actually had!”

“Yeah, me too,” I said.

At this point, what I call a ‘Korenesque incident’ took place, which almost immediately led to a prototype cartoon hurriedly sketched out on a napkin. (I have what I refer to as “the Collected napkins”). Seated immediately next to us, was a couple in their seventies, i would guess. They were quite elegantly dressed for a summer night in Vermont, more like people having dinner before going to the opera at Lincoln Center. They told the waitress that they were from New York. Then our waitress told Ed and I “tonight’s special;” it was sort of Reuben-like sandwich, served with fries. Ed was intrigued and ordered it. When the waitress set Ed’s meal on the table, the man of the New York couple leaned close, and promoting the obvious as a revelation, exclaimed, “I see you ordered the special.” A few moments, Ed’s narrative imagination thus incited, out came his notebook; soon on a small page appeared two Korenesque male figures having dinner; well over the confines of a plate, sprawled one of Ed’s decidedly Mesozoic creatures (with expressive hands), who, while clearly dead, still maintained a bemused expression. The aforementioned male New York interloper spoke the caption: “I see you ordered the special.”

For whatever reason, the notion, or phenomenon, of “withholding” came back around. Of course, the loose-knit reference was to that turtle withholding knowledge of love. Ed asked me what the most painful example of “withholding” was in my experience. I didn’t hesitate even a moment. I didn’t have to think about it. “My grandfather on my mother’s side,” I said. “He died when I was nearly thirty. But all during my childhood and after, there was all this talk about his having participated in the murder of a Dutch policeman who’s turned my grandfather’s closest friend — Meir Tal, who later became a rabbi. Turned Meir’s fiance in to the gestapo. She perished in a camp — in Holland. It’s a very very long story of woe. But basically I begged and pleaded with my grandfather to tell me the truth of what he’d done. I knew he’d done it. I really needed to understand what happened. Whenever I brought it up, which was often, he talked in circles. I eventually found out from Meir Tal at my grandfather’s funeral. But my grandfather withheld it from me. Personally, he withheld it. It was terribly painful.”

“I know you loved the guy, but he was kind of a nemesis, from what I’ve understood of it, what you’ve told me.”

“He was always just out of reach.”

The conversation veered off to here and there. Talking, we closed down the place. We talked more in front of the Kellog-Hubbard Library, where our cars were parked. “I’ve got what I consider a powerful withholding tale,” he said. “But I need to think about it a little. For the next time.” Starry sky on the drive home.

— Howard Norman

Howard Norman’s most recent novel, Come To The Window, is published in July, 2024 by W.W. Norton.