At The Oscars! Liza Donnelly Live-Draws From the Red Carpet

Back for her third trip to the Academy Awards, Liza Donnelly, is live-drawing for CBS News (she’s their Resident Cartoonist). You can follow her work tonight from the Red Carpet on Instagram (lizadonnelly), Twitter (@lizadonnelly), etc., etc.

________________________________________________

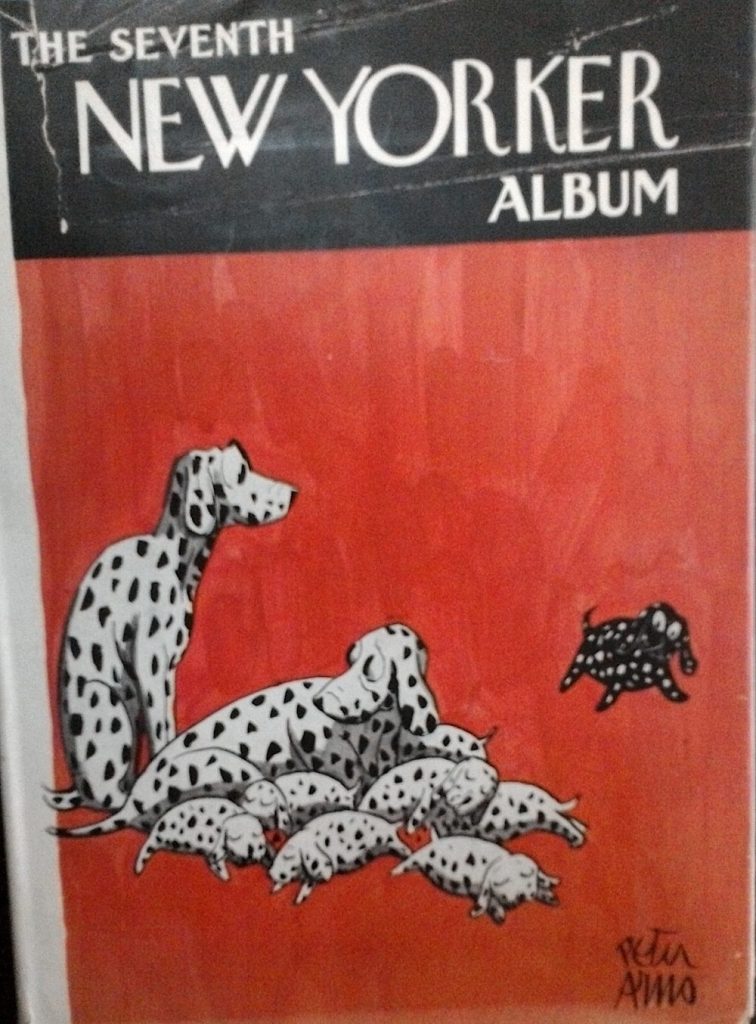

“That Special Kind of Madness”: The Seventh New Yorker Album

The Seventh New Yorker Album, published in 1935 by Random House, features Peter Arno’s March 23, 1935 New Yorker cover as its cover (the third solo album cover for Arno, with two more to follow). As I wrote in my Arno biography, this cover was “a quiet link between the old Arno style and what would become the new.”

The front jacket flap copy informs us that this album is a two-fer since there was not a 1934 album, and goes on to say, “Consequently, this edition not only contains more pictures by more artists, but the publishers believe that it marks a new high standard in quality for the series.”

A remarkable album in the series for one reason: it has dueling forewords: The Undertakers Garland (described as “A Dissenting Foreword By Lewis Mumford ” and Fresh Flowers (described as “A Partial Defence By One Of The Editors” ) .

Lewis Mumford, at the time the magazine’s Art Critic, didn’t sugar-coat his take on The New Yorker‘s current cartoons, writing, in part:

“…the jokes seem more interesting than the drawings; or rather, even when the drawings are most adequate, they remain a mere instrument of the idea….The comedy has that special kind of madness that springs out of a rough day at the office and three rapid Martinis. It is titillating, but a little frothy; it tickles me but remains peripheral; it has flavor but lacks salt.”

Wolcott Gibbs, who wrote the “partial defence” was in his fifth year of acting, in his words, “as a sort of liaison officer between the editorial staff of The New Yorker and the artists who draw its pictures,” addressed Mr. Mumford’s issues one-by-one and concluded with this “defence” of Mr. Mumford’s “three rapid Martinis” charge:

“This apparently refers to the work of a few artists whose characters belong to no particular land or time and are held to the world only lightly, by the pull of tempered gravity. They are the wilder shadows in the same wonderland that Lewis Carroll first explored, and they are valuable to this collection as lesser examples of the same universal and timeless comedy. It is, of course, important that this sort of humor, operating in its own particular vacuum, be used judiciously…”

And so, here we have, just ten years into the New Yorker‘s existence, a very public debate over what a New Yorker cartoon should be, and should not be. If there’s a constant in this funny world of the magazine’s cartoons — now closing in on their 100th birthday — it is that the debate has never ceased.

Here’s the list of the contributing artists in the album.

Most of the names will be familiar to long-time New Yorker readers, with the possible exception of Eric Monroe Ward, who is a certified member of Ink Spill’s One Club. The One Club is limited to cartoonists who have been published once and only once in the New Yorker. This icon ![]() identifies them on the A-Z.

identifies them on the A-Z.

Mr. Ward’s only appearance was in the issue of July 14, 1934. As his work likely has little opportunity to shine, I’m showing his one drawing below:

*Note: this very same issue with Mr. Ward’s drawing also contains James Thurber’s classic, “What have you done with Dr. Millmoss?” — for me personally, a most important cartoon — actually, the most important cartoon. Nice to run across it again in its natural habitat.

__________________

For more on Lewis Mumford, check out Findings and Keepings: analects for an autobiography (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975).

And for more on Wolcott Gibbs, there is Thomas Vinciguerra’s wonderful Cast of Characters: Wolcott Gibbs, E.B. White, James Thurber and the Golden Age of The New Yorker (Norton, 2016).