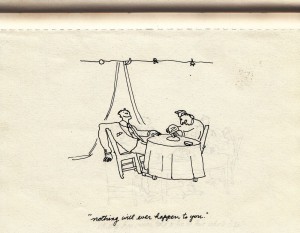

By July of 1977, when I cracked open a brand new sketchbook, I’d already filled 38 others with drawings that had yet to connect with The New Yorker‘s Art Editor, Lee Lorenz; in other words: I was still an unpublished cartoonist. Of course I didn’t have a clue that the brand new sketchbook, #39 (pictured above), would contain the drawing that changed my unpublished status, sort of. Twelve drawings into the book I drew a fortune teller telling a man, “Nothing will ever happen to you.”

I copied it, and sent in the copy with my weekly batch to The New Yorker. They bought it for its idea, and gave it to the incomparable Whitney Darrow, Jr. to work up in his great style. I was left with the mixed blessing of having sold something to The New Yorker, but having to explain to family and friends why the work published wasn’t mine.

Left: Whitney Darrow’s published version

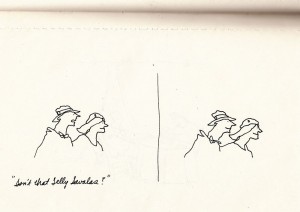

This post, however, is about the drawing in sketchbook #39 that came a page before the fortune teller drawing. In those early days I’d draw words and picture directly onto the sketchbook, without working them out somewhere. They all looked somewhat finished. Thus the sketchbook was a day-by-day unedited chronicle of work. Recently, I opened the sketchbook and looked at the drawing before the fortune teller drawing. It’s undoubtedly a personal tipping point, in just a turn of the page — it separates my years as an unpublished cartoonist from the years to come as a published cartoonist. It gave me a bit of a shudder looking at the drawing, a two-parter, captioned, “Isn’t that Telly Savalas?” What if (I let myself think) the next drawing after Telly Savalas hadn’t been the one; there’s not a hint of a possibility it would lead to a publishable idea. In a funny way, this little dance continues on to this day. There’s always going to be a Telly Savalas just before the drawing that works.

Who loves ya, baby?